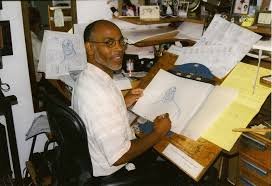

Last night my wife and I watched the hour-long PBS documentary Huz: Drawn to Life, about the life and work of Ron Husband, the first Black animator for Disney Studios who did work on such Disney classics as The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast.[1] It’s fascinating, and if you are able to watch it where you are I highly recommend it. Even if—like me—you are none too impressed with the cash-bloated IP warehouse that Disney has become, Husband’s story is inspiring as that of a life spent in the pursuit of creativity.

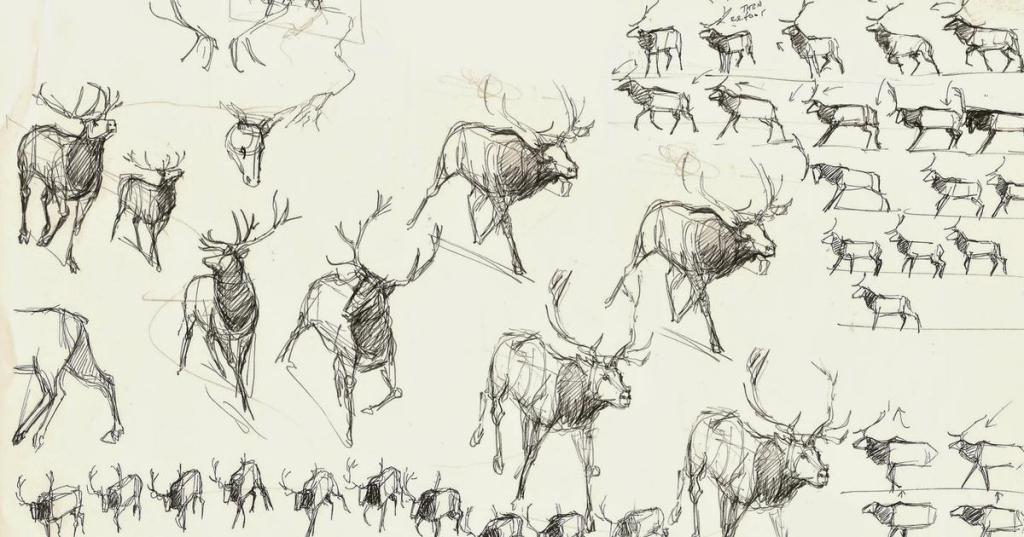

Huz focuses on Husband’s voluminous sketchbooks, which, we discover, he takes literally everywhere—so much so that his wife, LaVonne, says on camera that she isn’t worried about him taking up with other women because they would have to compete with his sketchbook. Husband is always drawing, always rendering episodes from his life, from his imagination, not as a nervous habit like people who doodle on the margins of their meeting notes but as constant, relentless practice. Husband says, “I look at my sketchbooks as practice, practice, practice. It’s practice won’t make you perfect. Practice just makes you better, and I wanna get better.”

It’s worth thinking about that Husband is saying these words as a retired legendary Disney animator. If anyone has the right to rest on their laurels and just go fishing, it’s Ron Husband. But that isn’t how he sees himself or how he lives his life. He is still drawing, still trying to “get better.” Much like Pablo Casals, the world-famous cellist who, when asked at the age of 81 in 1957 why he still practices cello four to five hours a day, responded, “Because I think I am making progress.” Or like the Ukiyo-e master Hokusai, quoted in Huz as saying,

From the age of 16, I had a mania for drawing all shapes of things.

When I was 50, I had published a universe of designs, but all I had done before the age of 70 is not even worth bothering about.

At 75, I have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, of birds, fish, and insects.

When I am 80, you will see real progress.

At 90, I shall cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself.

And at 110, everything I create, a dot, a line will jump to life as never before.[2]

What is it like to live this way, devoted to a lifetime of practice, not in the futile search for perfection but instead in search of patient improvement? Obviously it’s not for the success and accolades, not really; Husband, Casals, Hokusai had already received all of these things in their old age. Husband gives us a clue to the motivation in another part of Huz:

There’s a line in Chariots of Fire when Eric’s little sister asked him, you know, “Why do you run?”

He runs all the time and he says, “When I run, I feel God’s pleasure.”

And when I draw I feel God’s pleasure.

When Husband says that he “feels God’s pleasure” when he draws, I know just a little about what he is talking about. Not that I can draw. Not in the least. For me I “feel God’s pleasure”—that indefinable feeling one gets when one’s lonely mental striving breaks open something important about the world—in the constant struggle with words and ideas. I feel it when I write something especially apt. I feel it when, in my day job, I write a legal argument that is not only convincing and accurately states what the law is, but is also (to my ear) well-put to boot.[3] I feel it when reading also—especially when I am reading a sentence or paragraph in a language other than English (something I challenge myself to do from time to time) and the sense of a passage previously unclear to me snaps into clear focus, illuminating not only what the author is saying but also the language itself.

I am not as good at what I do as Ron Husband is at drawing and animating. There’s no point in my pretending otherwise. Yet this indescribable feeling of rightness, of sheer pleasure, still drives me and still makes what I do worthwhile to me, regardless of whether anyone reads my writing or whether our firm wins its case.

Writing and reading are not always sheer pleasure for me, of course. Sometimes they are drudgery; sometimes they are rushed, dashed off in order to meet a deadline, purely utilitarian, put out in a moment and forgotten. Sometimes they are an intensely uncomfortable struggle, like performing hand surgery on yourself with your other, non-dominant hand. But the moments, however rare, of “feeling God’s pleasure” remind me that the struggle is worthwhile. It’s worthwhile even if it yields me no other reward or public acclaim. At those times I know, in a way I know nothing else, that I have wrested words from the mute silence that reigned before the birth of humanity and that which will reign after we are all long dead, and in doing so, I have, however infinitesimally, pushed back the horizons of ignorance and hatred. I suspect that a similar knowledge drives other creative types also.

Others have written about the creative process more memorably than I have. Nothing I am saying is particularly original. I write about it here because, in watching Huz, I was overwhelmed by the thought: Husband’s life of creativity, of devotion to the struggle with a recalcitrant, never-to-be-mastered practice, is what our AI tech overlords want to take away from us.

The “promise” of generative AI—if “promise” is even the right word here—is that anyone with a decent internet connection can, by writing a quick prompt or series of prompts, generate an essay or image—possibly even a novel, or a whole film. Of course, it manages this feat by ransacking the near-entirety of the written word and large swaths of digitally available images and video without the consent of, or compensation to, its creators, and runs it through massive computer arrays that devour electricity and (ever-scarcening) water. But hey, content, in mere seconds!

There are so many legitimate criticisms of generative AI that I won’t even try to rehearse them all here. I will just limit myself to this one point: generative AI’s advocates look at a life like Ron Husband’s and seem to be saying, what a waste of time and energy! Wouldn’t it have been better to let computers do all of that drawing, in a mere fraction of the time, so that humans like Ron Husband could have spent their time doing something else?

I can’t speak for Ron Husband, but I can say for myself that even the implication that the creative part of my life is just a time sink that keeps me from lavishing attention on “something else” bespeaks an utterly impoverished view of what makes my being alive worthwhile. If anything, the truth of the matter is that things are exactly the other way around: those moments of creativity justify, for me, the dismal drudgery of commuting, paying bills, and feeding the meat puppet I inhabit three times a day in a way that doesn’t make daily life even harder than it already is.

After all, what is this “something else” upon which I am supposed to be lavishing all of this extra time? Buying and eating yet another new flavor of Oreo cookies? Watching one of the eighty-seven new shows Netflix dropped last week?[4] At best, I guess the answer is “spending time with loved ones,” but then, what are we supposed to spend our quality time doing? If, with each passing day, I shrink a little bit more into something resembling a null (and hence fungible) site of sheer consumption, what do I have to offer my loved ones in this “quality time” anyway? I think of family gatherings friends have told me about where all anyone has to talk about are the shows they are watching or how much the things they have bought cost.

Of course, the real answer to the question “what should you be doing with the time AI saves you?” that the billionaire overlords have in mind is “creating more economic value for us, your billionaire overlords.” It used to take you a week to write a meaningless report for your seven managers—now you can do a couple of those in a day, leaving you more time to make… more such reports, as many as you can before you are replaced by someone who will make the same reports for less pay. (Or the machine you used to make all those reports learns how to make them itself, so your superiors don’t have to pay anyone anymore.) Take your pay, use it to get credit, then spend more than you earn on consumer goods and housing, creating even more economic value for investors. (Because for decades now, the U.S. economy, and the value of its dollar as the world’s reserve currency, have been propped up, not by making anything, but instead by creating more household debt.) And while you run around, your electronic devices and those around you surveil you and your consumer choices, creating yet another market for your surveillance data.

It’s hard to live in our current world without contributing to the vast upward-wealth-transfer machine our current economic reality has created. I won’t offer you any easy escape route here.[5] What I can say, though, is that you can reclaim the humanity of a life like Ron Husband’s—one in which you struggle with something larger than you are. Set aside some time. Steal it if you have to. Pick up a pencil and a sketchbook. Practice a musical instrument. Start learning a foreign language, or improve one you already know a little bit. Read a book you think will be difficult to understand. Or something else entirely. It will be frustrating, even painful, at times. You will feel stupid, bewildered, and confused. That’s fine. Stick with it. And if it feels like it is coming too easily—slow down! You will probably not achieve mastery, but as the masterful artists I have referenced here teach us, complete mastery is illusory. Each achievement, each “level unlocked,” just opens up new horizons you have not yet reached and may ultimately never reach.

Again: this is fine. More than fine, actually: this is what feels like to be alive as a human on Earth. Trust that, somewhere in the struggle, there will be moments where you make or do something that surprises you, or where something makes sense in a way it didn’t before. When this happens, savor it; this is why you are doing any of it. This is why you are here. Share what you do with people—share it on the Internet, even!—but do not expect for a moment that any satisfaction you get from others’ reception of it will ever exceed that flash of satisfaction you feel when things fall into place. Because that is what “feeling God’s pleasure” is like.

[1] Full disclosure: we were directed to this documentary because we are friends with Yehudah Husband, Ron Husband’s son, who also appears in it speaking about his father.

[2] I am unable to verify the actual provenance or accuracy of this quote, which comes directly from the transcript of Huz. Similar versions of this float around the Internet, some with different ages listed. As the Quote Investigator site has (or should have) taught us all, quotations and their attribution have a mysterious life of their own.

[3] In my day job I work as a paralegal and office manager for a consumer advocate attorney. I draft all sorts of legal pleadings that the attorney then revises and files. Once in a great while my writing makes it into the public record of a lawsuit largely unaltered, but never with my name attached to it. It provides a constant lesson in humility.

[4] I need to clarify here that I love Oreo cookies and watch my fair share of television. Life can and should afford a certain quantum of passive consumption, mindless or otherwise. But a good life cannot just be that.

[5] Generally, anyone trying to sell you on such an escape route—especially Internet “influencers”—is trying to grift you, anyway.