At present I am making my desultory way through a collection of Marcel Proust’s critical writings,[1] the centerpiece of which is a collection of notes for a book-length work of criticism that would have probably borne the title Contre Sainte-Beuve (Against Sainte-Beuve). Proust’s writing abounds in observations on books and literature, but the writing collected in this volume contains his most sustained discussions of reading, particularly the experience of reading.

For Proust, there is nothing automatic, transparent, or facile about reading. Contre Sainte-Beuve, written in French, deals with French writers in its entirety, and yet he says: “The great books are written in a sort of foreign language.” He goes on to say that “beneath each word [of them] each of us puts our own reading [sens], or at least our image, which is often a misreading [contresens]. But with the great books, all the misreadings one makes are great.” Yet with care and diligence, one reads great works more than once, and one reads more books by the same author. Reading more than one book by the same author is, in fact, essential; in doing so commonalities become salient, habitual turns of phrase or characterizations, all of those things that go into our sense of a writer’s distinctive style, much as we perceive “the same sinuosity of a profile, the same piece of fabric, the same chair in two paintings by the same painter” which shows us “something common to both: the predilection and the essence of the painter’s spirit.”[3] The more we read, the more we realize, in a form of historical consciousness, that “in the same generation spirits of a similar sort, of the same family, of the same culture, of the same inspiration, of the same context, of the same condition, take up the pen to write almost the same thing in the same way,” and yet each “embroiders it in a particular way that is his own, and which makes the same thing completely new.”[4]

Contre Sainte-Beuve remained unfinished and unpublished at Proust’s death in 1922, so the work is fragmentary in form and undecided as to its overall literary conceit. Proust did seem to consider it at one point as a straightforward work of criticism under his own voice, but the chief conception that comes through in the notes we have is of a dialogue between Marcel, the narrator of In Search of Lost Time, and his mother. Even then it would have been largely a monologue; the notes we have contain no actual words assigned to Marcel’s mother. Written shortly before Proust began devoting his waning energies chiefly to ISOLT, it is unclear whether it would have been a preface to that work or its final part, its coda. In addition to Proust’s own takes on literature and criticism, we get introduced to preliminary glimpses of Gilberte Swann, Mme de Villeparisis, and the Count and Countess of Guermantes.

Proust more than once describes the Count of Guermantes’ love of Balzac and says that he has a full edition of The Human Comedy in his library that he inherited from his father. (This version of the Count of Guermantes, at least, has little patience for the vie mondaine of aristocratic society and hides in his second-floor library whenever the Duchess has guests.) Near the end of the notes on Balzac, the narrator writes:

I must admit that I understand M. de Guermantes—I who read the same way throughout my whole childhood, I for whom Colomba has been for so long “the volume from which one forbade me to read the Venus d’Ille” (“one,” I say, Mother—it was you!) Those volumes from which one read a work for the first time are like the first dress in which one saw a woman for the first time; they tell us what the book was for us then, what we were for it. Finding those volumes is the only way in which I am a bibliophile. The edition from which I read a book for the first time, the edition in which it gave me its first impression, are the only “first editions,” the only “original editions” in which I have an interest. It is still enough for me to remember those volumes. Their old pages are so porous to my memory that I am nearly afraid that they will also absorb my impressions from today and that I will no longer find in them my impressions from before. Every time I think about them, I want them to open themselves up to the page where I shut them near to the lamp or the wooden bench in the garden, when Papa told me: “Stand up straight.”

And I wonder sometimes whether the way I read today might still more closely resemble that of Mr. Guermantes than that of contemporary critics. A literary work is still for me a living whole whose acquaintance I make from the very first line, that I listen to with deference, to which I grant all rights as long as I am with it, without choosing or debating. [5]

For Marcel, the physical form of the book—not only the book’s binding, the look of its pages, but also its insertion into his physical space, its relationship to his body—are indissolubly part of the “living whole” of the book as read, not only part of the experience of reading it but also of the memory of what it says.

Marcel goes on to say that as he matured he began to extend this sense of the living wholeness of a book to encompass all of the books of an author—just that labor of comparison and noticing of commonalities he elsewhere says is part of the work of reading. In this, he says he has gone beyond the Count of Guermantes, whose sense of reading is so bound up with the physical form of the books in his library that he routinely confuses which author wrote a book because, in his library, books by several authors have the same binding:

[T]he library, M. de Guermantes’ father’s library, contained all of Balzac, all of Roger de Beauvoir, all of Fenimore Cooper, all of Walter Scott and the complete plays of Alexandre Duval, all bound in the same old-fashioned gold binding. The Count adored these books and re-read them often, and one could talk to him about Balzac without finding him at a loss. … But if one asked the Count [about Balzac’s novel Mademoiselle de Choisy], he would say: “I think Roger de Beauvoir wrote that.” He easily confused all these “charming” books that had the same covers, the same way that people mix up the senna and the morphine because they come in the same white bottle.[6]

Obviously collapsing the experience of encountering a literary work wholly into that of encountering a specific physical object at a specific place and time can go too far! In reading, we are in some part reading through the visible words to the meaning, which is, at some ideal limit anyway, the same regardless of the physical format in which we encounter the words. But this sensuous, physical aspect of reading—the conscious encounter with a specific copy of a book, published at a specific time, on a specific kind of paper, set in a specific font, read under specific conditions, is for me, as it appears to be for Marcel, an irreducible aspect of reading, the soil out of which all reaching for the ideal meaning of the words towards the “spirit” and music of the author grows.

This episode from Proust helped bring into focus for me why I have become so disenchanted over time with ebooks. In the 1990s and early 2000s, when ebooks went from public-domain text files without formatting and became formatted documents made available by publishers themselves, I was mildly intrigued. However, when I first bought a tablet in 2012 I was not only a convert to ebooks, but a sort of evangelist. The notion of owning a whole library of books that didn’t weigh anything or take up more physical space and that one could carry around everywhere fascinated me. I even contemplated the possibility of obtaining digital copies of all the books I had in my physical library and then getting rid of the physical library. It added to ebooks’ allure that in 2012 I was in a point in my life in which I had moved on an average once every two years and was very tired of schlepping between 40 and 60 boxes of books every time I got a new apartment.

Yet once I actually began reading more, ebooks really began to lose their luster. Yes, they are convenient. They are also a relatively inexpensive way to obtain books that in some cases would be difficult to obtain in hard copy. I still do about 25-30% of my book reading digitally. But I still find them unsatisfying, and when I expect that a book will be especially enjoyable or useful or important to me, I obtain a physical copy of it whenever possible.

What changed for me was intimately related to the experience of reading ebooks. To get at what I am after, think about what it’s like to read a print book. A print book is, before it is anything else, a discrete physical object. You hold it in your hand. It has mass, and the longer it is the more mass it has. The covers and the pages have a texture, a color, a smell, a thickness. In reading it, your body has to make certain accommodations to it: you have to hold it a certain way, at a certain distance, under a certain kind of light for it to be legible, you have to support one side of it more than the other depending on whether you are nearer the beginning than the end, and so forth. It is literally another body situated in space alongside my body, a foreign body one handles, maneuvers, cradles, caresses. And different books, like different bodies, have to be handled differently. The brand-new paperback I bought demands to be treated differently than the tiny, fragile 1804 copy of Ossian’s Poems I bought from a library sale in 1993.

Needless to say, ebooks are not like this. Of course, ebooks are physically instantiated; they aren’t utterly non-physical. The machines (computers, smartphones, tablets) we use to read ebooks are also physical. But their physicality is, with respect to the reading experience, negligible and largely indifferent. The machine from which I read an ebook is just a platform that displays to me, now one ebook, now another. The experience of reading one ebook is more or less like reading any other. For that matter, if I am reading the ebook off of a device I use to do other things, the experience of reading the book is functionally the same as all the other things I do on the device—read and receive e-mail, do work, make phone calls, read and post on social media. All of these things happen within the four corners of the same screen on the same device. The computer, phone, or tablet remains the same physical object in the same physical configuration with respect to my body no matter how much or how many books I read on it.

This fact about computing gives rise to a different sense of the space in which an ebook is located. Computing tasks—all ebook reading is just a kind of computing task, of course—all take place in a space contained within one or more physical screens that depending on the device one is using is called a “desktop” or a “home screen.” (I will just refer to it as a “desktop” from here on out.) The programs one opens—the e-book reader, the web browser, the e-mail client, and so forth—open within and on top of this desktop. The desktop’s height and width mirror those of the physical world our bodies inhabit, but depending on the platform we are using, they may be slightly bigger than what we can see of it through our screen. (On a Windows PC, for instance, one can move a window for an application so that a large portion of it extends off the screen into void, invisible space.) The strange feature of this space, though, is that its depth functions in ways wholly unlike that of physical space. The background image of one’s desktop functions as the ground, the bedrock, over which one can layer as many application windows as the computing power of one’s device will allow. None of them have the slightest thickness; having fifty windows open on one’s screen is spatially the same as having one open, or none.

One’s relationship with this strange quasi-physical space of computing that resembles, but is not the same as, our own, to which our screens give us a limited window, is, when you think about it, completely indirect. Before the advent of touch screens, manipulating what happened on the screen involved pushing physical buttons (on a keyboard or mouse) and moving tracking devices (the mouse) which would then make something happen in the computing space. Touch screens have not eliminated this indirection; they have only changed it. One still has to tap on the screen in just the same places one had to click on using one’s mouse previously. On completely touch-screen environments like smartphones or tablets, tapping or swiping with one’s fingers does not always yield the results one would get in the physical world. Tapping or swiping the screen in one application does one thing in one application, another thing in another, and sometimes, depending on the device, swiping brings up entire screens related to the operating system that half the time one didn’t even ask for. In other words, rather than mimicking physical manipulation, touch-screen devices convert physical gestures into yet another set of quasi-linguistic commands with a physical “vocabulary” one has to learn in order to use the devices competently, and that one has to re-learn when one switches between platforms with different operating systems.

When it comes to ebooks, the quasi-physicality of computing space together with the largely arbitrary physical “vocabulary” of gestures used on touch-screen devices utterly deprives the reading experience of its physicality, its resistance, its thickness. It’s like reading a book hermetically sealed under glass, whose pages move at a command but which one can never hold, never touch. It’s actually a little worse than that, because in a physical book, even one in a glass case, the words are fixed on the pages where they are printed. In an ebook one reads off of an e-reader like a Kindle, Nook, or other tablet, the location of the words on the page and what they look like are fluid and fungible. One can change the font, the font size, the margins, even whether the background “page” is white, sepia-toned, or black (if one is reading off of a color device). Make a change to any of these, and the position of the words on the screen of text one is reading move. (Sometimes, depending on the ebook’s formatting, they even move without making any changes when one swipes forward to a later page and then swipes back to find one’s place.)

Admittedly, the adaptability of text presentation on ebooks is a great advantage for neuroatypical readers or readers with visual issues, since they can make books accessible in ways that most physical books are not for them. I am definitely not glossing over that—nor am I arguing for the abolition of ebooks! (As I said previously, I do at least 25% of my reading off of an e-reader.) It’s just a different experience for me, and one that is impoverished for me in a lot of ways. I have a hard time savoring writing off an e-reader. I tend to read off an e-reader solely for the ideal content of the words, not the sensuousness of what the words say. Most of my e-reading tends to be nonfiction now that I think about it.

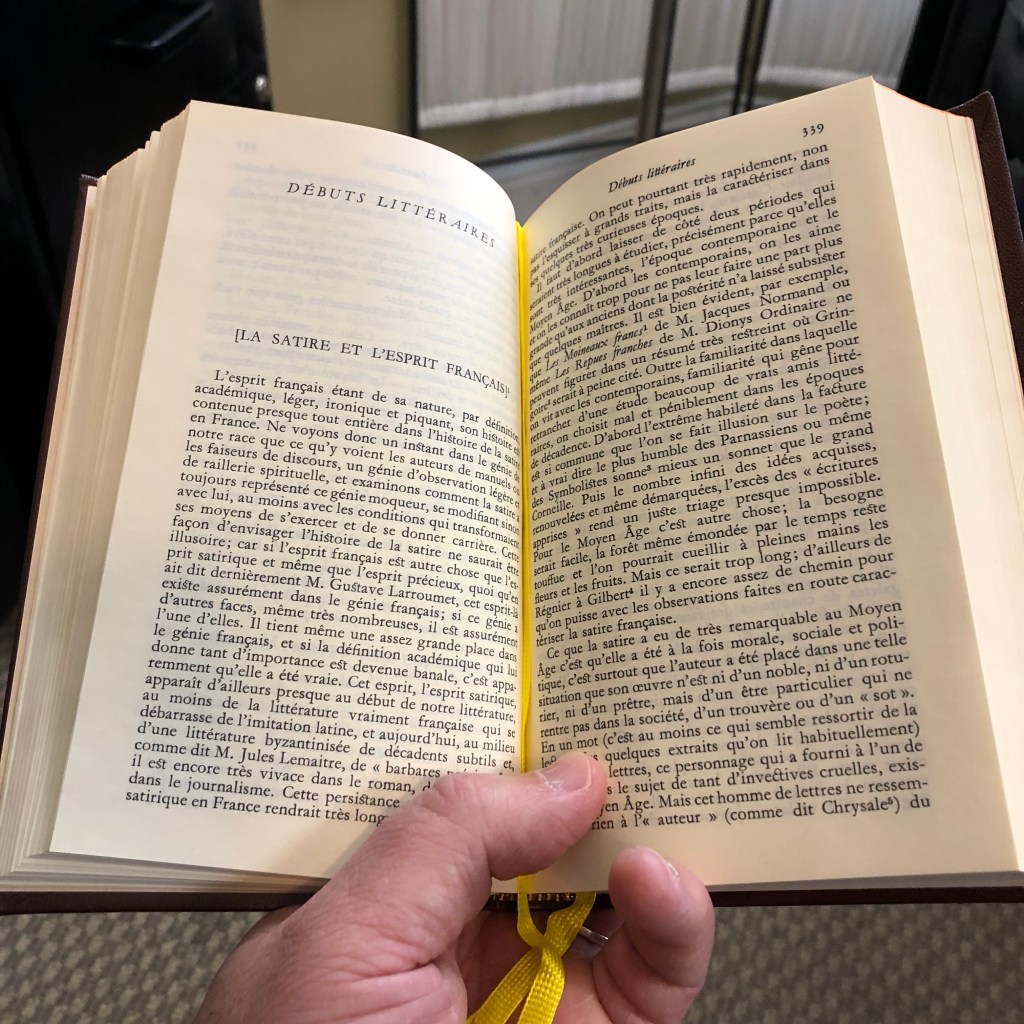

In ebooks I join the author in what she means to say, but the reading doesn’t bring my body along with it. I miss the kinesthetic experience of physical books—of the words I read, the paper they are printed on, the weight of the book, the sense of anticipation I have when holding open the first few pages of a book I just started, the feeling of clearing the halfway point, the lightness in my right hand as I near the end. (Or in my left hand, if I am reading manga!) More subtly, though, I find myself missing the difference between books—the yellowing mass-market paperback of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie from the 1960’s I just read versus the leather-bound, bible-paper elegance of the Pléaide edition of Contre Sainte-Beuve I am currently reading. On my e-reader, all ebooks, even PDFs that give literal scanned images of physical pages, feel somehow interchangeable, like scraps of a single vast ocean of context-free text. (A fact about electronically stored text that large-language AI models have, of course, exploited.)

Perhaps I am just a cranky old man consumed by nostalgia for his past. Physical books, after all, are themselves a technology that has undergone numerous transformations in history.[7] Holding up one form of the book as somehow sacred is historically blinkered, to say the least. Yet the advent of ebooks has not led to the demise of the physical book, as presaged in the late 2000’s and early 2010’s. Print books, at last report, still vastly outsell ebooks. It can’t be the case that all of those physical book buyers are just buying them to show on Instagram or TikTok or to use as interior design accessories. Something endures about the physical book format.

Or, as Proust puts it, those porous book pages are still soaking up our memories, our impressions, our thoughts, all of the embodied reactions we have when we encounter the words of another in reading.

[1] Proust, Marcel. Contre Sainte-Beuve précédé de Pastiches et mélanges et suivi de Essais et articles. Ed. Pierre Clarac et Yves Sandre (Gallimard (Pléiade), 1971). I identify all citations to this volume as “Sainte-Beuve” followed by a page number. All translations, and hence all translation errors, are entirely my own.

[2] Sainte-Beuve, p. 304.

[3] Sainte-Beuve, p. 304.

[4] Sainte-Beuve, p. 306.

[5] Sainte-Beuve, p. 295.

[6] Sainte-Beuve, p. 297.

[7] Irene Vallejo provides a colorful anecdote-filled account of this history in Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World (Knopf, 2022).

Leave a comment