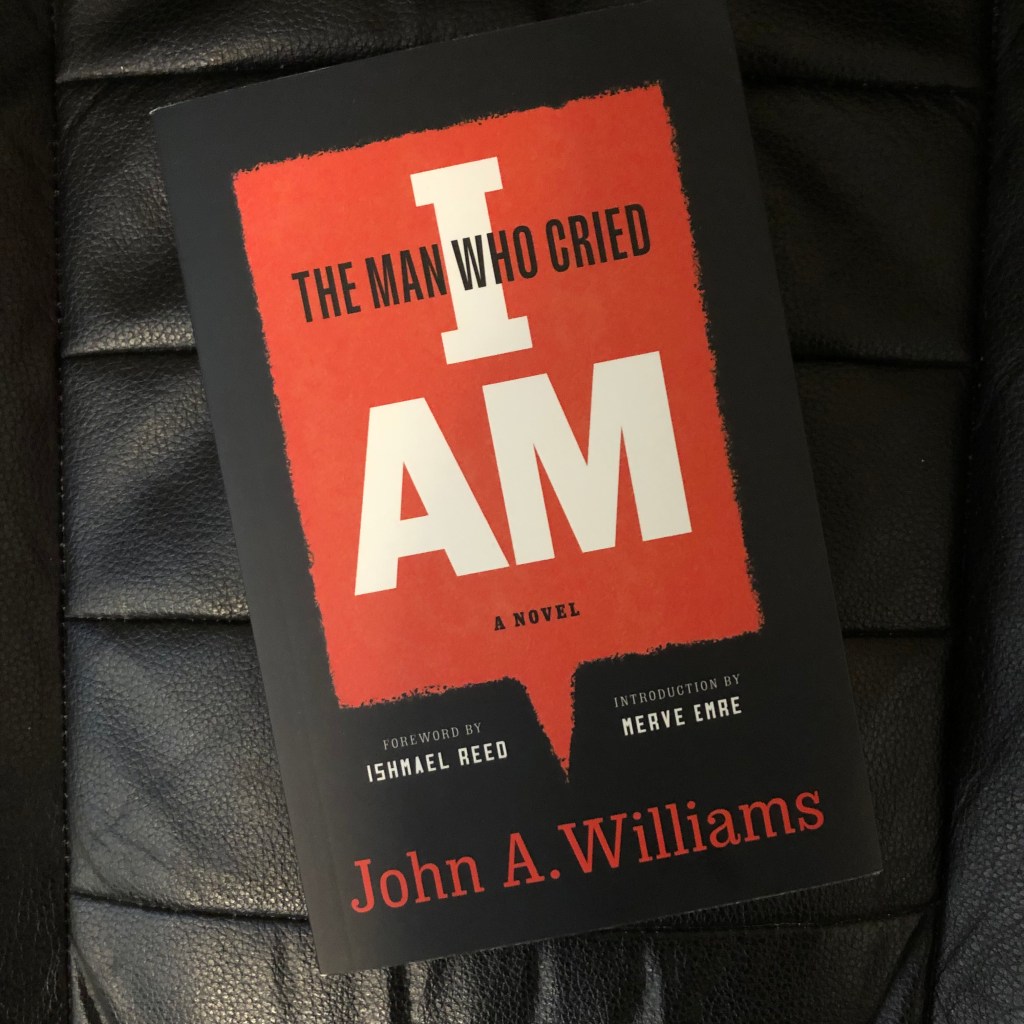

Williams, John A. The Man Who Cried I Am: A Novel. Library of America, 2023.

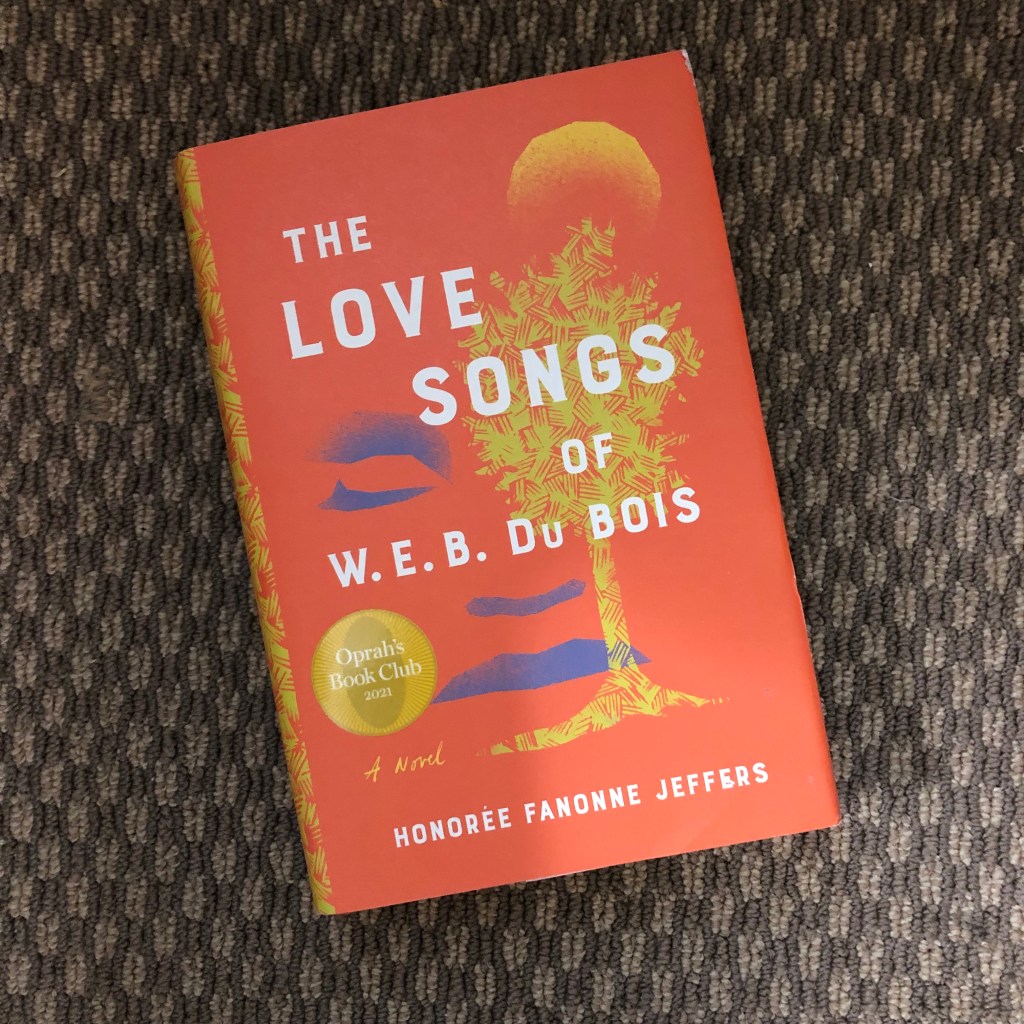

Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois. Harper, 2021.

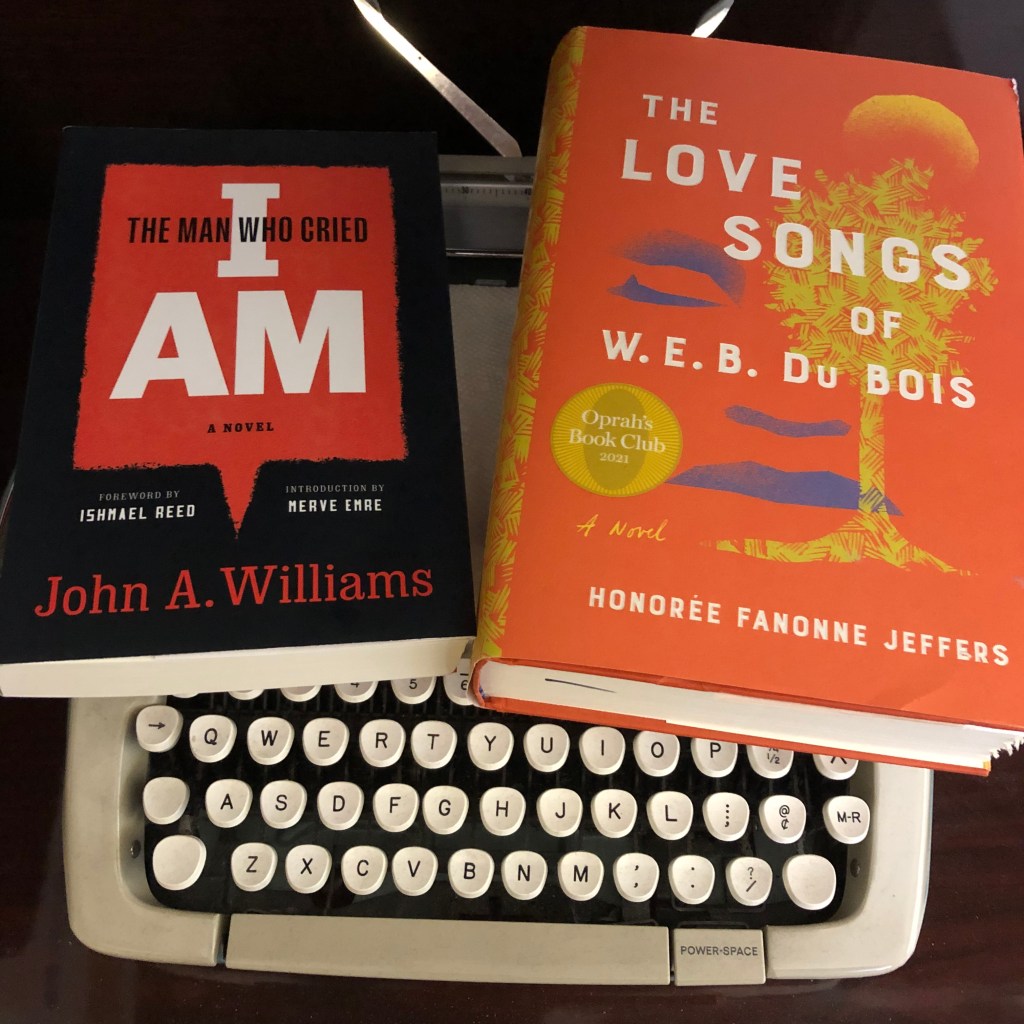

I did not set out this February to read two books that furnish a starkly contrasting view of the Black American experience; it just turned out that way. John A. Williams’ 1967 conspiracy-theory novel The Man Who Cried I Am, reissued in 2023 by the Library of America with a foreword by Ishmael Reed and an introduction by Merve Emre, feels about as far as one can get from Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ sweeping 2021 family/historical epic The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois. The contrasts, though, are oddly illuminating of the ways in which gender norms intersect with race.

***

The LOA’s reissue of The Man Who Cried bills it as a forgotten classic. It tells the story of Max Reddick, a Black American writer and journalist, who we find dying of rectal cancer and reminiscing on the flotsam and jetsam of his personal and professional life during a visit to Europe for the funeral of his friend, the famous author Harry Ames. (The Man Who Cried is, among other things, a roman à clef with many characters torn from real life, and the expat-in-France Ames is obviously modeled on Richard Wright.) While he catches up with his estranged wife in the Netherlands and with other friends he shared in common with Ames, Reddick discovers that Ames bequeathed him documentary evidence of a top-secret US plan, King Alfred, to round up Black Americans in concentration camps and/or to exterminate them in case the civil rights movement went too far for White comfort. Ames, he discovers, was murdered for his knowledge of this information. Reddick, now himself in danger of his life, just manages to leak evidence of the plan to Minister Q, the novel’s equivalent for Malcolm X, before he is murdered for what he knows. The novel ends on an ambiguous note, implying that the American government’s murder of Ames and Reddick signals the beginning of King Alfred’s implementation, but giving no inkling of its success or failure at its genocidal aims.

It’s a rather long novel and the vast majority of it happens before the unveiling of the King Alfred plan. Reddick, who is loosely modeled on the author himself as well as Williams’ friend and fellow author Chester Himes, takes us via his reminiscences through a turbulent career. Even without the conspiracy theory twist the story takes, the novel is a fascinating and sharply opinionated take on the Black literary scene in postwar America. A common refrain is that the white-dominated literary world will only accept one Black writer at a time, and in the late fifties and early sixties it is Ames (i.e. Richard Wright). The goal of every other Black writer is to dethrone Ames/Wright so that they can get their turn being “the one.” As Marion Dawes, a very unflattering and churlish depiction of James Baldwin, puts it to Ames’s face: he has to kill the father to take over, and Ames/Wright is the father he has to kill. It’s a rather bare-knuckle, cynical take on the famous literary feud between Wright and Baldwin, reductive, perhaps, but also a contemporary (and today under-represented) take on the context behind the feud nonetheless. It’s interesting to know that this take exists, even if one thinks (as I do) that it grossly simplifies Baldwin’s motivations and the merits of his critique.

The book is also pretty unabashedly misogynistic and homophobic. Reddick and Ames womanizers to the end (a lot of sex happens in this book, very little of it with anyone’s actual “official” partner), and very few woman characters are introduced with a description other than the attractiveness, or lack thereof, of their physical attributes to Reddick. Reddick’s last wish for sexual conquest is to have sex with a redhead, a wish that (spoiler alert) is destined to remain unfulfilled. Reddick’s view on Black women writers is curtly dismissive. Dawes/Baldwin and other literary “faggots” earn little more than Reddick and Ames’ ridicule. And so on. The misogyny and homophobia are not really the point of the book; they’re casual, like the air (and the second-hand smoke) the book breathes. It’s just jarring to read in 2024, and was likely more than a little jarring in 1967. As Ishmael Reed writes in his Foreword, “If #MeToo ever had truth and reconciliation forums, I’d be on trial with the rest of the guys” (xx).

The Man Who Cried is also a social and political novel, and not just when it comes to the King Alfred plan. Reddick’s journalistic career gets put on hold in the early 60’s when he accepts an irresistible invitation to join the speechwriting team of an unnamed president (who is clearly John F. Kennedy). Reddick quits in disillusionment when the president’s commitment to civil rights is decidedly lukewarm, a fact that in the world of the novel makes perfect sense once the contours of King Alfred come to light. Reddick then resumes his journalism job and works the civil rights movement beat, covering not only Minister Q/Malcolm X but also Paul Durrell, a thinly veiled stand-in for Martin Luther King, Jr. Reddick dislikes and distrusts Durrell, finding his political stance too reactionary and deferential to White feelings and his personal life dangerously messy. He has far greater respect for the radicalism, non-pacifism, and personal rigidity of Minister Q, which is why, when the genocidal aspirations of the US government become clear, Reddick entrusts what he has learned to Q in hopes that he can organize an appropriately militant response to King Alfred in time.

The Man Who Cried is a hard-boiled, paranoid thriller that is a little enervating to read, but in 1967 it had the ring of literary truth for a lot of people. Williams ran pages from his (fictional) King Alfred plan in New York newspapers as advertisements as a publicity stunt, which led many people to confuse, War of the Worlds-like, the fiction for reality. Emre’s Introduction to the 2023 LOA edition even relates that Clive DePatten, a young Chicago man associated with the Black Panther Party, testified in 1970 before a committee of Congress that he thought the King Alfred plan was real, leading the committee to observe that no, that plan was from a work of fiction. In our time, right-wing conspiracy theories are in the ascendant, including the “Great Replacement” theory that is almost a color-flipped version of King Alfred, and so this novel’s conspiracy theory feels odd, almost quaint. The left speaks now of systems, of neoliberal “best practices” that everyone seems to take as so self-evident that they don’t bother to cover them up, of standard diplomatic and economic policy that of late has made the US Israel’s de facto—and sometimes, literal—defense lawyer while it seeks to liquidate the Palestinian populations of Gaza and the West Bank. We now know that the odds that anyone could hide a plan of the magnitude of King Alfred in official Washington in 2024 is nearly nil, but that it really doesn’t matter; the problem today is a glut of information, a confused, benumbed population incapable of sorting through it all, and a full quarter of the US electorate for whom no countervailing facts will ever overcome their self-absorbed sense of grievance. Official secrecy hardly matters anymore. Yet a book like this serves as a lurid reminder in our times that America still lives in a tense relationship, not only with Blackness, but also with the workings of state power.

***

It is hard to imagine anything more removed from the hard-nosed, solitary, misogynistic, paranoid world of The Man Who Cried than The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois. In Love Songs, Jeffers paints a panoramic picture of the life of Ailey Garfield, a contemporary Black woman, and that of her ancestors back to the 17th century in what would become the state of Georgia. It is definitely a woman-centric book—there are plenty of men, but women drive the story—but it is not even remotely all sweetness and light. Many of Aliey’s ancestors are enslaved, and the book does not soft-pedal both the vivid horrors and routine humiliations her ancestors endure. Love Songs is also clear-eyed about Ailey’s White ancestors and their relationship to her story through rape and, occasionally, love, but love warped by the unquestioned power Whites enjoyed in the American South both before and after the Civil War. To boot, a central motif of Ailey’s story involves child sexual abuse; her most prominent White ancestor was a prolific abuser of children, and she and her sisters also endure being sexually abused as children by their paternal grandfather, Gandee. This book stares a lot of pain and injustice squarely in the face.

But what makes this book feel so different from The Man Who Cried is that it is leavened by a sense of hope, a sense that connecting with one’s ancestors is powerful, a sense that Black women have survived terrible things and that, together, they will keep surviving. Jeffers proudly wears the feminist/womanist influence of Alice Walker (and before her, Zora Neale Hurston) on her sleeve. As in Walker and Hurston, and unlike Williams’ novel, formal politics and political actors play virtually no role in the story. The story is not impervious to such matters; Emancipation and Reconstruction happen, of course, as well as Jim Crow, the civil rights movement, and even the Black militancy of the 1970’s. These things, though, aren’t really the point in Love Songs. Jeffers’ Chicasetta, Georgia, the ancestral home of Ailey’s family, is remarkably like Hurston’s Eatonville, Florida in this respect: a world where Black folk, and especially Black women, live their lives aware of, and wary of, White folks but unencumbered by the White gaze in their daily living.

Williams is haunted by the specter of White America deciding to liquidate the ten percent or so of its population that is Black. Love Songs observes, though, that by blood, by history, and by culture, Black and White (and Native American) folk in America are so intertwined that even the effort to extricate them from one another mentally requires Herculean feats of denial, intentional obfuscation, and bad faith. Forget about actually doing it!

Racism is definitely a theme in Love Songs—the episodes from the second half of the book when Aliey begins graduate school in history and encounters White Southern history grad students are cringeworthy and priceless—but unlike in The Man Who Cried, its perpetuation isn’t the work of a conspiratorial cabal among the security apparatuses of world governments. It is what we now call “structural” racism, that ghostly set of taken-for-granted practices and structured ignorance and privilege that is so hard to combat precisely because no single institution implements it according to a plan.

***

Certainly some of the difference between The Man Who Cried and Love Songs is the benefit of what the past few decades have taught us. Love Songs was published over forty years after The Man Who Cried, and the terms of what Charles Mills has called the implicit “racial contract” structuring race as a social category have just changed. For that matter, so has the sex and gender contract. The male characters in The Man Who Cried, if not the entire book, could be read, not without justification, as mid-century machismo and its projections run amok. Reddick literally does cry “I am” at multiple points in the novel, and his sense of what it means to “be” is in these moments agonistic—a cry for his enemies to come forward, name themselves, and grant him the dignity of stating their case against him to his face. To face him “like a man,” in other words. At the end of the novel, he gets his wish, dying not of the rectal cancer eating away at him but assassinated by an acquaintance who he has discovered is working as an agent of the King Alfred plan.

Love Songs, though, presents a very different sense of what it means to “be” in this strong sense. Aliey discovers not only who she is by exploring who her ancestors were and what they did and suffered. She discovers that in this search for the ancestors, even those who set themselves against one as enemies are among one’s ancestors as well, showing that their taking up the position of adversary rests upon their own alienation from and refusal to acknowledge their own pasts. And at least some of this alienation is the result, not just of the fictitious but socially valent discourse of race, but also of gender and its norms. Multiple men who cross Ailey’s path in Love Songs are much like Max Reddick: damaged, not only by the omnipresent reality of structural racism and its many consequences, but also by the straitjacket of their own gendered expectations.

But Love Songs at least holds out an example of Black masculinity outside these straitjackets: Dr. Jason Hargrace, Ailey’s uncle and mentor who she knows from childhood as “Uncle Root.” Uncle Root is a retired history professor at Routledge College, the fictional HBCU in Georgia which Ailey and one of her two sisters attends as an undergraduate. Uncle Root is genteel, wise, a defender of W.E.B. DuBois who acknowledges the liabilities of DuBois’s elitism, and a sort of proto-feminist. In a recurring motif in the book, Uncle Root even takes the last name of his wife, Olivia, in an echo of the matrilineal Creek society of the family’s Native American ancestors. Uncle Root’s Black masculinity is not premised on drawing out an enemy for direct combat, but instead in patience, wisdom, and support, especially of Ailey and the other women in their family.

I did not deliberately set out to read these two books so closely together. They both just happened to rise to the top of my reading pile near one another. Yet it’s now hard for me to think about the issues they both raise without thinking of the tension field that exists between the two. It’s odd how sometimes one’s occasional reading works out like this in ways one never would have expected. This is why I rarely make elaborate reading plans or set terribly specific reading goals. Sometimes the most incongruous books yield the most interesting insights when put in conversation with one another.

Leave a comment