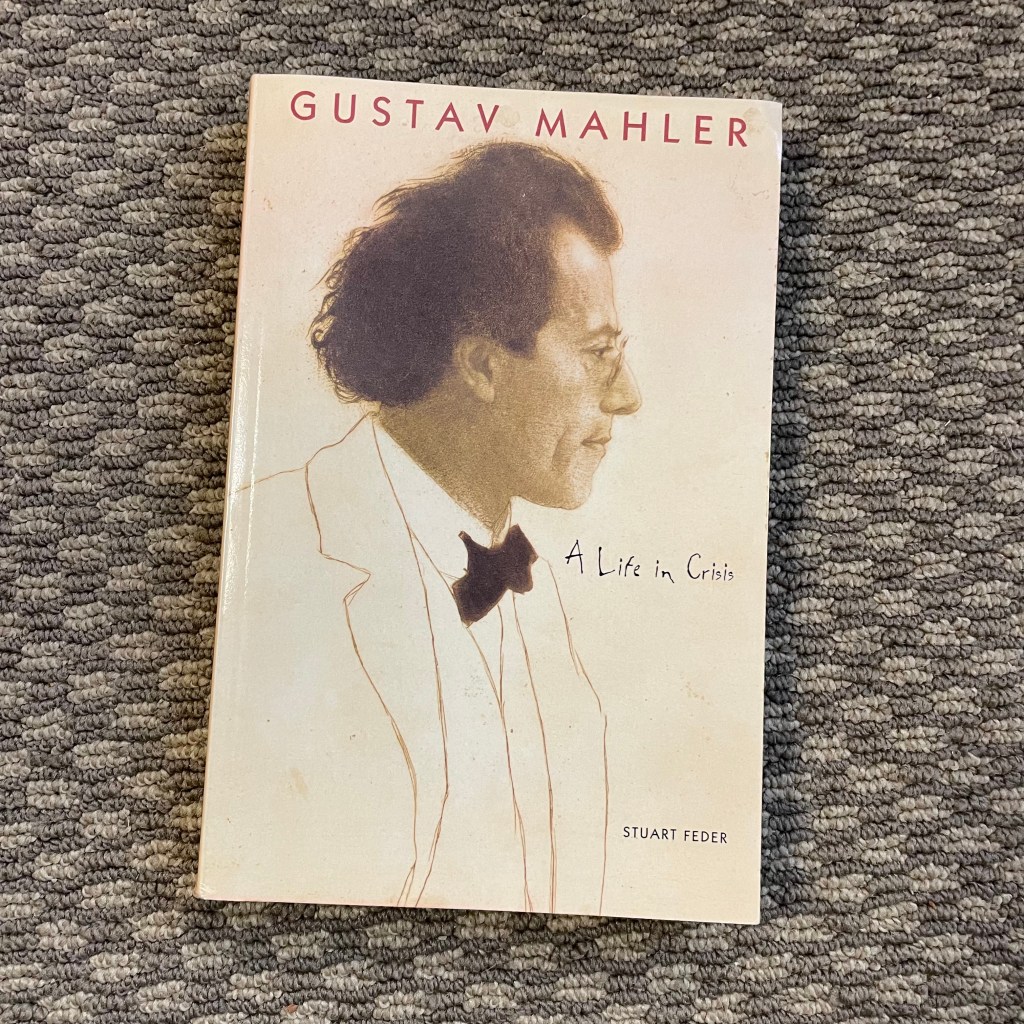

Feder, Stuart. Gustav Mahler: A Life in Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Gustav Mahler’s music has left subsequent generations grasping for handles to grab in order to understand it. It abounds in contradictions—lush sensuousness alongside loud cacophony, vast symphonic themes punctuated by cow bells and musical kitsch (klezmer, military band music). It is extraordinarily dramatic and unique, with a sound that borrows widely from late Romantics such as Bruckner and Wagner and at the same time little resembles anyone who came before him.

It is unsurprising, then, that many have looked to Mahler’s biography to gain traction on the immensity of the music. The biographical route yields a great deal of information; Mahler spent a long career in public life as an orchestra conductor, and both his professional and private lives are well documented. Memoirs of those who knew Mahler at varying periods of his life also abound, and in recent years Henry Louis de la Grange wrote a massive, all-encompassing multivolume academic biography.

Faced with the sheer profusion of biographical work on Mahler that already exists, other biographers are faced with the choice of reinventing the wheel or organizing a biographical study around a specific focus. Stuart Feder’s Gustav Mahler: A Life in Crisis follows the latter course. Feder ostensibly organizes his biography around certain “crises” in Mahler’s life. Feder’s real aim, however, is to apply Freudian psychoanalysis to Mahler and his work, and especially to Mahler’s marriage to Alma (Schindler) Mahler-Werfel, as well as to examine the (tenuous) relationship between Mahler and Freud himself.

The results of Feder’s study are convincing enough, given the purposes that animate it. Feder doesn’t, however, provide much insight into Mahler’s artwork, with a few exceptions (more on that below). In order to get to his real area of biographical interest—Mahler’s courtship of, and marriage to, Alma, in the last eleven years of his life—Feder is obligated to pass over the first four decades of Mahler’s life and career in spectacularly cursory fashion. Bare numbers of pages tell the tale. The book, exclusive of acknowledgements, indices, and the like, is 315 pages. It treats Mahler’s entire life prior to meeting Alma—years in which he wrote the Wunderhorn songs and his first four symphonies—in the first 91 pages. Many of those 91 pages are spent stage-setting Mahler’s first meeting Alma.

As the book’s narrative proceeds, the focus on Mahler’s marriage—and the now-infamous role Alma played in it—becomes virtually exclusive. In some of the best researched and most vivid sections of the book, Feder dissects Alma’s famous affair with Walter Gropius and its effects on Mahler, documenting how, contrary to Alma’s later vagueness on the subject, the affair continued for the remainder of Mahler’s life and after his death with the active support and assistance of Alma’s mother, Anna Moll. Indeed, in the last quarter of the book Mahler himself, ailing and heartbroken, recedes largely into the background as Feder takes obvious jouissance in detailing the perfidy of Alma and of Anna Moll. In Feder’s account Anna is especially treacherous, living vicariously through Alma’s sexual exploits while at the same time hiding them from Mahler and acting as a maternal figure to him. (Anna and her husband Carl, the Epilogue tells us, become raving antisemites; Carl, a supporter of Hitler and National Socialism, committed suicide in April 1945 as the Red Army neared Vienna.)[1]

The obvious climax of the book is Mahler’s one and only four-hour-long walking conversation with Sigmund Freud in 1910. The book foreshadows this meeting at some length, and yet as a narrative climax it is underwhelming. Mahler, himself skeptical of psychoanalysis, only agreed to talk to Freud during the personal crisis induced by the Alma-Gropius affair. As it turns out, very little is known about the substance of their conversation in this meeting or of its ultimate effect on Mahler, but if you want a fairly comprehensive inventory of what is known about it, this book has it. There are no known notes from Freud of this conversation, and he only alluded to it briefly on a couple of occasions long after Mahler’s death. It is far too much to say that Freud “psychoanalyzed” Mahler in the strict sense; that isn’t something one does in a single four-hour walk around town, not even if one happens to be Freud. In effect, Feder’s book is an attempt to reconstruct what Freud might have concluded about Mahler had Freud had the chance to analyze him at proper length. Despite the paucity of the evidence, Feder nevertheless claims that Freud’s one meeting with Mahler yielded him significant therapeutic benefits—a claim I sincerely doubt.

Regardless of whether psychoanalysis benefited Mahler in the last year of his life or not, Feder’s psychoanalytic reconstruction provides only scant insight into Mahler the artist. A lot of people endure, as Mahler did, a great deal of childhood trauma only to end up in bad marriages. Not all of them achieve fame in their own lifetime and leave behind a wildly idiosyncratic and hugely influential legacy of artworks. Feder does have very interesting observations about Mahler’s youthful work Das klagende Lied, and the pages he devotes to Das Lied von der Erde, especially to the conclusion of the final song, “Der Abschied,” are possibly the best part of the book. Feder does discuss Mahler’s incomplete sketches of the Tenth Symphony at some length, drafted as they were at the height of his marital crisis, but he is as much, if not more, interested in them for Mahler’s marginalia about Alma and his own state of mind as he is in their music. The remainder of Mahler’s music gets only brief and relatively superficial discussion. The premiere of the Eighth Symphony in Munich in 1910, happening as it did at the height of the Alma-Gropius crisis, gets far shorter shrift than it deserves, given the role it played in Mahler’s career as a public figure as well as that symphony’s role in the social and political life of pre-World-War-I Central Europe. That story is told better elsewhere.[2]

The effect of Feder’s chosen focus on Mahler’s family life becomes almost stifling as the book nears its end. No doubt as Mahler’s life ended he was, personally, reduced to a pathetic, almost childlike state by his ill health and the unresolved tension of his marriage. How to square this reality with Mahler’s artworks and his public-facing life is hard to resolve, and this book doesn’t really accomplish it. If anything, I came away from this book feeling like I knew less about how the various aspects of Mahler hang together, if in fact they hang together at all. Perhaps this book reminds us that there are simply limits to what biography can teach us about artistic creation.[3]

If you want an account of the marriage of Gustav and Alma Mahler that puts it into the context of their broader family life, this is your book. In fact, this could be the best single study of that subject available. If you have a wider interest in Mahler’s life in the light of his art and its significance, though, this book is bound to be disappointing.

[1] Feder is remarkably unsympathetic, in my opinion, to Alma Mahler-Werfel in this book. Granted, she comes off badly in the detailed account of her affair with Gropius. In her defense, she married Mahler when she was twenty (he was forty), and what person makes their best decisions in their twenties? Despite Feder’s best efforts, I see the Alma that emerges from his pages as someone who was trying to live life on her own terms in an era when women had vanishingly narrow options other than just finding a man to marry and having his children. Her relationship with Mahler, and with his legacy after his death, was, to put it generously, complicated, but on the whole Alma deserves better than simple high-minded opprobrium. For a feminist reclamation of Alma’s life, see Haste, Cate, Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

By contrast, Anna Moll sounds pretty terrible no matter how you slice it.

[2] Karen Painter’s work on the Eighth Symphony is especially enlightening; see her “The Aesthetics of Mass Culture: Mahler’s Eighth Symphony and Its Legacy,” 127-157 of Painter, Karen, ed., Mahler and His World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), and Symphonic Aspirations: German Music and Politics, 1900-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

[3] The most famous single discussion of Mahler’s music that largely brackets the details of his biography has to be Theodor Adorno’s 1960 Mahler: A Musical Physiognomy (Edmund Jephcott, English translation, University of Chicago Press, 1996). Interestingly, Feder’s book is the only one on Mahler I know of written after 1996 in English that doesn’t at least mention Adorno or his book even once.

Leave a comment