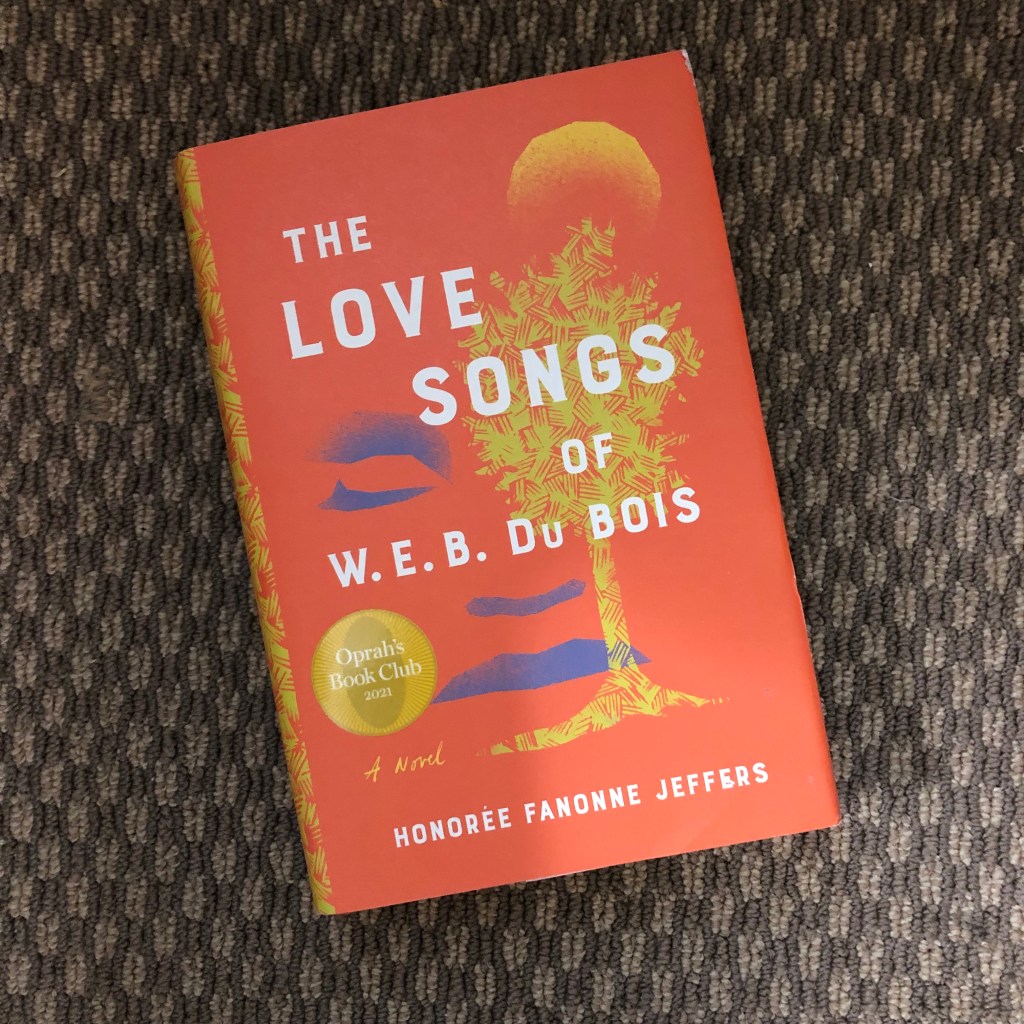

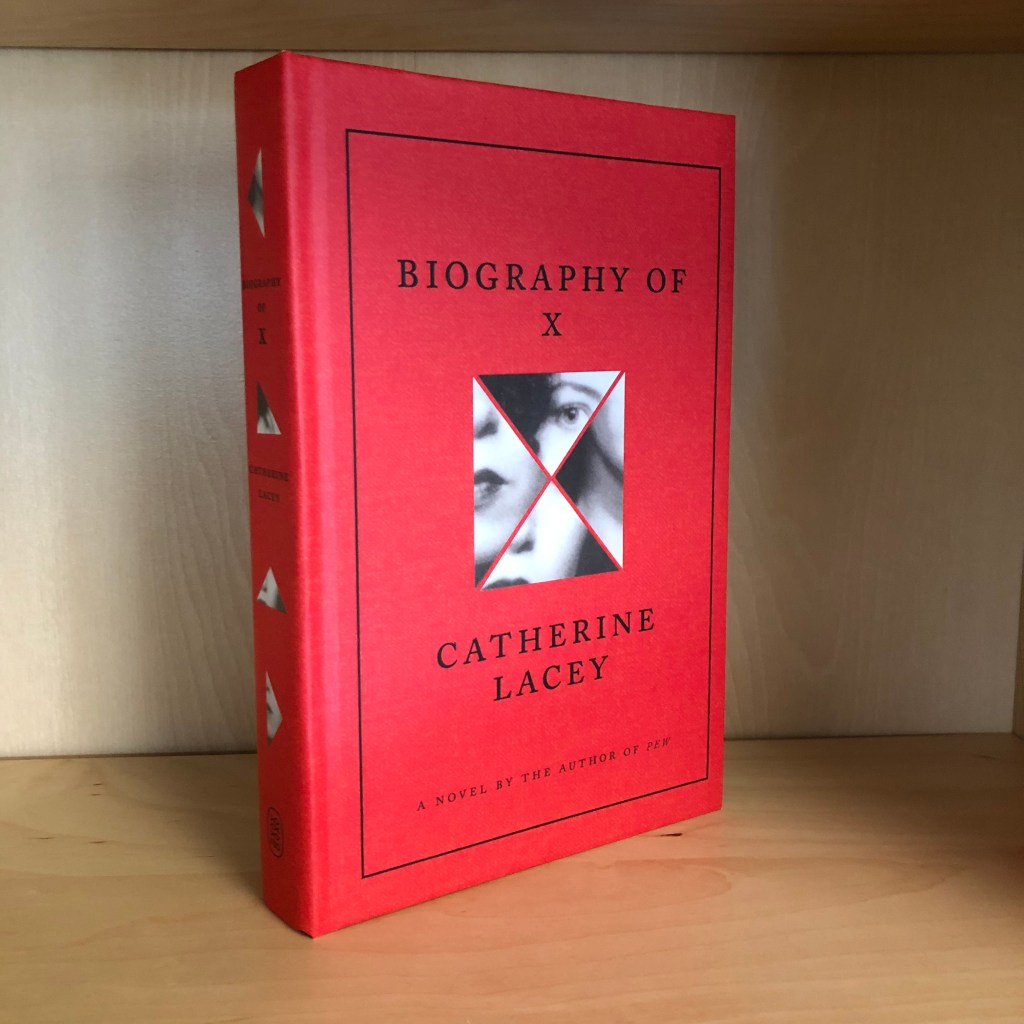

Lacey, Catherine. Biography of X (FSG, 2023).

“Then she said this one thing I’ve thought of many times since—‘You have to know what you’re leaving out in order for it not to be there. Otherwise, it’s not an absence, it’s just nothing.’”[1]

At a moment in Catherine Lacey’s alternate-history novel Biography of X (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2003), the title subject, a Protean woman who late in life simply referred to herself as “X,” has impressed Tom Waits enough for him to bring her to recording sessions at Electric Lady Studios in 1974. She amazes Waits and the rest of the studio with her inscrutable, mercurial style, which the narrator of the novel (her widow, C.L. Lucca) parses as a front she put up to play for time while she learned how to use the controls of the mixing board. As the episode with Waits in 1974 floats out of the narrative, Lucca writes:

At the time of the Waits session, four years after Jimi Hendrix’s death, many at Electric Lady felt Hendrix’s emanation hanging around. Several were convinced that Hendrix’s ghost was responsible for blessings and curses, but no one was sure if Bee [the pseudonym under which X was working at the time] was the former or the latter. (186)

The narrative of the novel has reached 1974 after a tour through the 1960’s. In the novel’s imagined counterfactual history of America, much of the 1960’s and early 1970’s counterculture and its literary and music scene has happened as it did here—folk music, Bob Dylan, protest songs—but the role of black folk in this period barely appears. This is the only mention of Hendrix in the entire book, and he is dead, a ghost, a spectral presence in the studio while she serves as a muse to Tom Waits.

This small episode encapsulated both what I found so interesting and, ultimately, so frustrating about Biography of X. It is an entertaining, playful, and suspenseful romp through the artistic and cultural avant-garde of the American sixties and its aftermath, at the same time as it invites us to think through our cultural and political present through the lens of a different version of American history. The trouble, though, with this latter invitation is that the alternate America of X is deeply, profoundly divided along most of the same lines as our America, but, unlike in our America, race appears to play virtually no part in either creating the divisions or shaping the self-understanding of those most committed to maintaining them. As an invitation to rethink America’s past and present, black folk in X are, like Jimi Hendrix in the quote above, ghostly presences, capable of blessing or cursing from beyond the grave but of, it seems, little else. And, with respect to the fictional quote from X above, the book leaves several hints that race is a genuine, carefully contrived absence in the narrative, not a mere nothing.

What that absence is trying to say, however, is unclear.

***

It is possible to read Biography of X the way one might read, say, Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code: that is, simply take for granted the factual premises the characters themselves take for granted, bracket those premises’ inherent implausibility, and get lost in the narrative, the characters, the events. In other words, read it simply as speculative fiction. At that level, the novel is both a great mystery story and a compelling portrait of a damaged, unlikable, cruel person and the abuse she metes out on virtually everyone in her life. (I have mixed feelings admitting that I have known people very much like X.) Yet it’s possible, and in fact much easier, I suspect, to tell a story like this without inventing an entire alternate history of the United States from the early 20th century forwards. (The film Tár leaps to mind.) It would seem that the elaborate counterfactual scenario Lacey invents isn’t just sci-fi style “worldbuilding,” but is instead part of the point the book is trying to get across. As such, it deserves some analysis in its own right.

The broad outlines of X’s alternate history of America are as follows. On Thanksgiving Day 1945, as the United States was emerging from World War II, a secret cabal of Southern state governors suddenly put into action a plan they had been carrying out in secret for a decade. A swiftly erected wall formed a border between, roughly speaking, the states of the old Confederacy and the rest of the nation. The new seceded South re-christened itself the “Southern Territory” (“ST” for short), and, as Lacey writes, by mid-1946 the rest of the country, rather than fighting a new civil war, simply let the ST secede and attempted to isolate it diplomatically. The remainder of the country broke up into the Northern Territory (which seems to have comprised most of the US north of Tennessee and east of the Mississippi) and the Western Territory, which encompassed the rest. The Northern and Western Territories enjoy more or less pacific relations with one another, and the Western Territory has a “laissez-faire” policy towards the ST, but the relationship between the North and the ST are antagonistic and governed by tense and draconian treaties. Specifically, emigration out of the ST is strictly forbidden, and attempts to cross the border lead invariably to summary execution.

The grounds of the ST’s secession are chiefly theocratic. In the America of X, Emma Goldman, far from being a harried, occasionally imprisoned anarchist revolutionary, is a pragmatic, yet still very progressive, socialist who moves from being governor of Illinois to chief of staff to FDR. She is assassinated in 1945, but not before leaving an indelible mark on the politics of the Northern Territory by means of her political activities and her essays. Under Goldman’s influence, the New Deal is far more progressive than that of our America, and in the America of X, the ST secedes largely on the stated rationale that American New Deal politics went too far to the left. In an act with practical and symbolic resonances, Southerners in X’s America bomb projects initiated by the New Deal Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1937, plunging what later becomes the ST into literal, not just metaphorical darkness. (The ST never gets widespread electrical service; a purported nighttime satellite photo prepared for the book dated 1993 shows the entire southeast of the continent in total darkness, surrounded by the bright lights of the other territories.)

The Southern Territory in X, though, is modeled more on the Puritanism of Hawthorne and Henry Miller than it is on the actual Jim Crow south. Church attendance becomes mandatory; expressions of questioning and doubt are penalized; a Stasi-like network of informants, the Guardians of Morality, keep tabs on the entire populace. The ST, we learn, by its formal end in 1996 incarcerated nearly half of its population at some point in their lives. Lacey adds, almost as an afterthought, that of course this extremely punitive situation fell harder on black folk than it did on white, but there is no sense that criminality in the ST was, as it was in the actual American South in this period, a thoroughly racialized matter. Racial disparities were merely a difference of degree, it seems, not of kind. The book makes no mention of segregated institutions and public accommodations, the hallmark of the Jim Crow South. There is a mention, in passing, of anti-miscegenation laws, but they aren’t portrayed as revealing something important about the ST. It’s just portrayed as of a piece with the explicitly theocratic oppression that falls on pretty much everyone in the ST; preachers are power brokers on a par with governors and legislators, and public professions of faith are the coin of the realm.

The Northern Territory is, by contrast, politically and socially progressive on a far more aggressive timeline than the more liberal areas of the actual United States. Early on, the Northern Territory abolishes sex and gender discrimination (including in employment and compensation), legalizes same-gender marriage, provides universal health care, provides universal basic income, and (we learn) very nearly abolishes prisons.[2] A recurring theme is that more subtle biases and discriminations still exist, but the formal legal framework is robustly anti-discrimination. However, even the descriptions of the Northern Territory do not make considerations of race central, other than to observe that it, too, has its own lingering legacy of racism, as it does for all of the invidious forms of oppression. But the ST is also, improbably, in one way far more progressive than the Northern Territory; for a time in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the ST had a formal program of reparations for descendants of enslaved persons, something that neither the Northern Territory nor the Western ever attempted.

By the time of the novel’s present (2005), the ST had collapsed under the weight of its ignorance and paranoia in 1996, was reinvaded by the Northern Territory, and is on the path to an uneasy “reunification” (not reconstruction—don’t call it reconstruction!) with the north. (Reunification with the Western Territory is not even mentioned as possible or desirable.) There are echoes of post-Civil-War Reconstruction, especially in the form of a counterpart to the KKK, the American Freedom Kampaign—spelled with that “K,” I guess, so we won’t miss the parallel—who carry out acts of terrorism in support of re-secession and assassinations of their enemies. It is telling, though, that over the entire course of the novel, the only named victims of the AFK are white people, mostly escapees from the former ST with whom they sought to settle old scores.

***

This alternate-history backdrop is an intriguing act of imagination, subtly portrayed. Biography of X is certainly a well-crafted novel. And I think one could just take the imagined history in X at face value and simply appreciate the way in which its characters’ lives are shaped by it. After all, it’s a made-up history. Who could tell Lacey she is wrong about it?

No one, certainly; and yet the readers of this novel will undoubtedly bring their own sense of history to her novel in search of potential lessons about what might have been (and hence what might be today). What we find, then, is a history shorn of many of the familiar landmarks we now take for granted. There is no Vietnam War[3]; no civil rights movement, no Dr. King; no Huey P. Newton, no Black Panthers, no Angela Davis; for that matter, no 9/11 and no wars in Afghanistan or Iraq. Nor is there the engagement that the New York art and cultural scene of the novel’s 1960’s heyday had with any of these subjects: no James Baldwin, no Nina Simone. The cultural linchpins of X’s alternate late 20th century are David Bowie, Kathy Acker, Susan Sontag: Europe-facing white artists and intellectuals.

All of this might, of course, just be an act of simple omission. A story need not be about everybody and everything, after all; stories that try risk reaching Forrest Gump levels of farce. (There is, for example, no mention or even hint of the 1969 New York Mets in this book, and it is, I suspect, better for it.) And yet, there are nagging hints in the case of race of a carefully structured absence, not just a mere omission. Start with the very title of the book. Biography of X’s whole conceit as a novel is that it is a biography/memoir published by X’s widow also titled Biography of X. How anyone could hear that title, especially in light of the period in time it covers, and not think of the Autobiography of Malcolm X?

Yet Malcolm—who, like X in the novel, took on the name “X,” although for very different reasons—is very nearly absent entirely from the historical narrative. But not entirely. In one episode, our narrator goes to Maine to interview a former FBI agent who claimed that X worked with him in the 1960s and 1970s on espionage missions to the Southern Territory. The book itself reaches no firm conclusions about whether X really did this—the FBI agent is elderly and a little bit doddering—but the book doesn’t close off that possibility either. Our narrator writes:

When I later learned that the letter “X” was used on internal FBI documents as a stand-in for agents’ real names, I again considered that there had been some sort of misunderstanding, and perhaps she’d never worked for the bureau. Then again, that, too, might have been a coincidence. “X” was often used in such a way, a placeholder for people or things discarded, hidden, or unknown. Malcolm X, Madame X, solving for x. (262)

This quote is the novel’s only flirtation with confronting the resonances of its own title head-on, and it is, it seems, deliberately vague. We don’t really know how or who Malcolm X was in the world of the novel, although one can only assume that he achieved fame under that name, rather than under the name Malcolm Little, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, or some other. So we can infer that in this world he joined the Nation of Islam, from whom he adopted this naming convention as a way of representing his unknown ancestors. But Malcolm himself, in our history, was about more than that lack of knowledge of what his ancestors were called. Indeed, one can read his Autobiography as a profound meditation on working out just who one’s ancestors actually are, on finding what really belongs in that placeholder. On solving for x, as it were. (There is a reason Alex Haley pivoted from editing the Autobiography to writing Roots.)

The X of this novel is, however, engaged in almost the opposite endeavor: that is, that of destroying the self by refracting it through a limitless set of simulacra so much and so often that the line between self and simulacrum threatens to break down. (Or seems to; there is a stable core of manipulativeness and violence to X throughout all her manifestations, a certain pleasure she takes in the discomfort and fear of others.) It feels like a stretch just too far to suggest that X is a sort of inverted negative of Malcolm X, and yet there is a sense in which this is true, a sense in which the novel itself invites such a comparison. But it’s a comparison that, like most of the rest of Biography of X’s engagement with race, consists of a frustrating absence, an absence that refuses to speak.

Much of X’s principled stands, such as they are, turn on a steadfast refusal to take on an identity and to allow her work to reflect, enhance, and grow out of that identity. In other words, she is vehemently opposed to what we would, in our time, call “identity politics.” In a way, the alternate American history Lacey puts into Biography of X mirrors the wish list of liberal and left-leaning critics of identity politics in our times: one in which identity-based oppression is merely an embarrassing artifact of individuals’ atavistic biases, rather than a structural (and personality-structuring) element of society. Were I wanting to be extremely uncharitable, I would read Biography of X’s portrayal of X and her relationship to the background history as a sort of fantasy for the Ricky Gervaises and Bill Mahers of the world, self-satisfied white people tired of exhortations to “wokeness” and of DEI programs when they feel like they have bent over backwards enough already.

Yet X is not offered up as a hero in this book. Far from it. And there are hints that, beneath it all, X herself may have come to view her estrangement from struggles against racism and contention with race (an estrangement shared, perhaps, by her society) as a genuine problem. The fictional biography of X we are reading dates from 2005, nine years after X’s untimely death. Fairly early on in the book, we learn that at her death X left written instructions that “the only people who would be allowed unfettered access to X’s archive and permission to use it in any way they pleased were the founding members of BASEL/ART, that is, the Black Americans for Southern Equality and Liberation through Art, Resistance, and Terror.” (116) We then learn that this group of artists is the only one for whom X has unmitigated praise. And yet, the novel does not flesh out this tantalizing lead. We learn a little about some of the artistic program of BASEL/ART and its members, but we don’t really learn anything about what makes their art or their program “black.” The only (imagined) work of art the narrative examines is a piece of performance art that criticizes and subverts the ST’s theocracy and religious practices, not its anti-blackness.

***

One famous reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is to read its racist tropes and the near-silence of Africans in the novel as a sort of critique of the colonialist mindset, dragging it out into the light of day and making us confront its bankruptcy, as readers, from within. I think in the case of Conrad this gives him far too much credit, but one might ask the same question about what Lacey is doing in Biography of X. Is this book a portrait of what it’s like to follow through a certain rejection of stable identity—the sort of project that is, after all, so much easier for a white person in our society—all the way to its end, where we realize that it is an abject failure? Is that the message of its imagined alternative history—that a color-blind version of American history is more telling in its absences than in what is present in it?

Maybe. That is, it’s possible to read the book in this way. It’s also possible to read the dialogues of Plato as a series of tantalizing hints at an esoteric doctrine the master carefully declined to commit to writing. As a friend in graduate school put it, shrugging his shoulders: it’s a reading, I guess. But Biography of X doesn’t force us to read it this way, and it’s possible to read it otherwise. It’s hard to say. Which is to say, if that was the point of the book, it demands a lot of uptake from the reader.

The book was published in 2023, at a time when a large enough portion of the United States would be comfortable with a neo-fascist white nationalist government that dispensed with democratic niceties and norms. The USA claimed in 2020 and 2021 to have engaged in a “reckoning” with its racist past and its continuation in the present in the form of police violence. American publishing treated the reading public to a spate of books about race and racism that purported to forward this crucial public conversation. And yet, Biography of X, one of the more critically lauded novels of 2023, all but writes the history of race and racism in the US out of existence, leaving it in, if at all, solely as the negative space in a sketch. It’s hard not to see both this book and its critical reception as US publishing and criticism’s way of saying: We’re bored with the racism conversation now; let’s move on.

Another writer, Thomas Mann, wrote a diagnosis of his own country’s descent into fascist chaos while in exile. In Doctor Faustus, like Biography of X a fictional biography attributed to another writer, in Mann’s case Serenus Zeitblom, a friend of Adrian Leverkühn, the temperamental and difficult artist at the center of the work. Near the end of his descent into syphilitic madness, a metaphor for Germany’s descent into the horrors of National Socialism, Zeitblom describes for us Leverkühn’s last work, The Lamentations of Doctor Faustus. Zeitblom sums up the work as a sort of inversion of, or reversal of, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, that exuberant icon of pan-European humanism. It “more than once formally negates the symphony, reverses it into the negative.”[4] Mann, at least, writing in exile as Germany spearheaded the near-destruction of humanistic Europe, affords the reader the clarity of knowing just what we are supposed to make of this project. America has a long way to go in its dance with its own racist and authoritarian demons. Will we look back on Biography of X as a sort of Doctor Faustus-like diagnosis of our times? Probably not. As a symptom of our times, however, it is a thoughtful and fascinating read.

[1] Biography of X, p. 240. All other citations to the book will be contained in parenthetical citations containing only a page number, e.g. (240).

[2] The queer politics of the novel are, interestingly, stuck somewhere around the 2005 of the actual United States for all that. There is not even a mention of nonbinary gender identities, transgender folk, or any of the other flashpoints of contemporary identitarian politics in 2023 and 2024. With possibly one exception: After the Tom Waits episode, X falls into David Bowie’s orbit and helps produce what becomes his 1977 studio album Low. One of the other producers with whom Bowie is already working is “Brianna Eno,” a gender-swapped version of Brian Eno, one of the actual co-producers of Low. In the world of X, was Brianna Eno simply a cis woman, or an AMAB trans woman? The book breezes past this question, perhaps as if to say that it isn’t really an interesting one to ask.

[3] Improbably, in the course of her research into X’s life our narrator meets a former FBI agent and State Department official who, we learn, participated in the diplomacy that averted war in Vietnam.

[4] Mann, Thomas, Doctor Faustus (Vintage Books, 1948), p. 490.