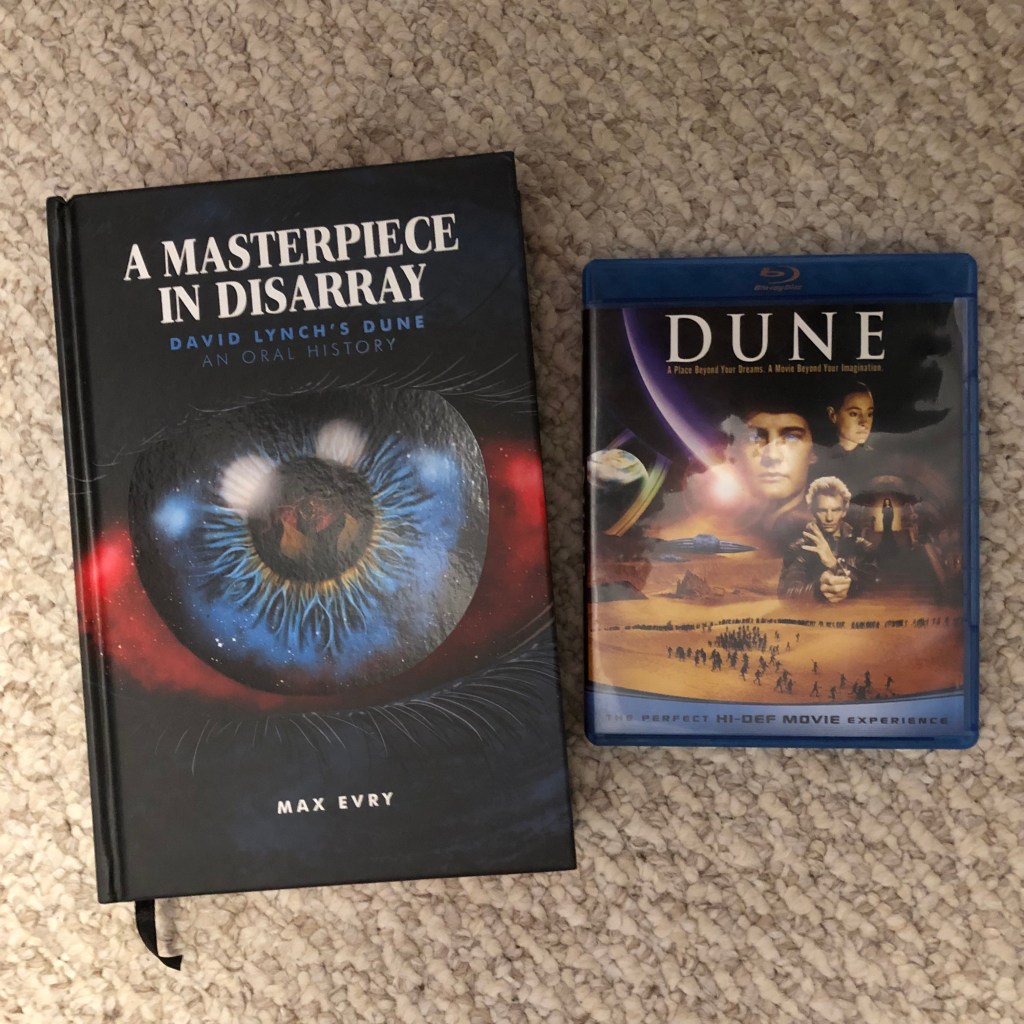

Evry, Max. A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch’s Dune. An Oral History (1984 Publishing, 2023).

Any number of feature films have been released in theaters in versions so truncated that they are nearly incomprehensible. Two examples of this always leap to my mind: Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World (1991), and David Lynch’s Dune (1984). In the case of Until the End of the World, at least, we now have the benefit of Wenders’ five-hour director’s cut, courtesy of the Criterion Collection. Having loved the 1991 theatrical release of Wenders’ epic road movie in the face of quite a lot of ridicule, and knowing its flaws, the director’s cut was, to me at least, a revelation of what could have been.

No such director’s cut is forthcoming for Dune, even though a fan edit that restores a great deal of cut footage exists. Max Evry’s A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch’s Dune. An Oral History (2023) gives us, among other things, a glimpse into why that director’s cut will likely never happen. Even if you don’t like the film enough to care about seeing a longer version of it, Masterpiece offers a glimpse at the way studio filmmaking worked in the early 1980’s, when Star Wars had already changed the rules of the game, for better or for worse, and the studios were racing to catch up. Films simply aren’t made like this anymore, and reading this book made me nostalgic for the version of Hollywood we get in the book, one where oddballs and hustlers could get a major studio to throw money at them to make a bizarre movie in the hope that it would stick. This book has no mention of focus groups, of creative decisions made with foreign distribution in mind, of crossover franchising—it’s just Lynch and Raffaella and Dino DeLaurentiis and a bunch of other weirdos in a literal sandbox in Mexico playing with millions of dollars.

Lynch’s Dune was not the first attempt at adapting the 1965 Frank Herbert novel. Perhaps the best known was Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ambitious but abortive 1970’s project, the subject of the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune. In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, though, the blockbuster success of Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back had all of the studios searching for what might be the next epic sci-fi adventure franchise. Famed producer Dino DeLaurentiis decided that it could be Dune and its many sequels. After all, Star Wars had cribbed so much from Dune that Frank Herbert himself had even contemplated suing George Lucas. What DeLaurentiis and company had in mind was that Dune, adapted for the screen, could become a Star Wars for adults.

The real weirdness of the making of Dune, when compared with 2024 Hollywood, begins with how David Lynch ended up directing it. At one point, Ridley Scott was attached to the project, but he decided to make Blade Runner instead (another sci-fi classic that, like Dune, suffered from studio interference). Lynch had developed a small but devoted art-house following in the industry from making Eraserhead and The Elephant Man—so devoted, in fact, that by 1981 and 1982 Lynch found himself in considerable demand from the major studios. He was on a short list to direct, if one can believe this, Fast Times at Ridgemont High (!), and George Lucas himself was courting him to direct Return of the Jedi, the third of the original Star Wars trilogy.

But DeLaurentiis and Dune won out. Evry’s account, which is pieced together from interviews, reporting from the time, and other available sources, suggests but does not firmly conclude that Dune was, of all these major-studio courtships, the movie Lynch really wanted to make. It hints that Lynch really had little interest in Return of the Jedi, a film all of whose artistic decisions had already been made before production even began, but he strung Lucas along for a long time in order to use Lucasfilm’s interest in him as leverage over Universal, DeLaurentiis, and Dune. If so, the stratagem worked—at least as far as Lynch and his creative team getting the movie off the ground, which is more than previous attempts to adapt Dune had managed to do.

The long story leading from pre-production to the release of the film, which comprises the bulk of the actual oral history in Masterpiece, is in effect the story of Lynch and his creative team running up against the limits of what a major studio was willing to do in 1983 and 1984. Universal and DeLaurentiis pumped a lot of money into Dune, and Lynch, as we now know with the benefit of his subsequent career, has a definite artistic vision, one which he brought to bear on Dune and which was blessed by Frank Herbert himself. The original hope, consistent with the Star Wars-like blockbuster franchise model, was that Dune would be the opening installment of a franchise that would eventually adapt Dune Messiah and Children of Dune. (As Masterpiece discusses, the studio even planned and marketed a series of tie-in action figures and toys, something I had completely forgotten.) As anyone who has read those sequels to Dune knows, though, that story isn’t the feel-good Joseph Campbell-style Journey of the Epic Savior Hero that Lucas baked into Star Wars. It is, in fact, a cautionary tale of the dangers posed by the (ahem, white) Epic Savior Hero narrative when wedded to advanced technology and geopolitical ambitions, a ciphered criticism of the colonial adventures of the European powers in the Middle East. A story for adults, definitely, and apparently the story Lynch was prepared to adapt for the screen.[1]

The film, however, began to fall foul of the inevitable limitations of what a major movie studio hungry for smash hits would finance before principal photography even finished. Some of the problem was sheer cost, of course, a concern compounded by the fact that the Dune Lynch had in mind would have been at least three, possibly four, hours long. Add to that the fact that the film was being made before the advent of cheap, relatively easy CGI visual effects, and that the production had to switch visual effects companies right as the post-production VFX stage started, and the business side had a real problem on its hands. Masterpiece is careful not to draw firm conclusions or to point unambiguous fingers on this most sensitive point—it merely quotes the principals interviewed at length and lets the reader decide—but the picture that emerged for me is that both Universal and DeLaurentiis blinked in tandem early in post-production, albeit each for slightly different reasons, and forced Lynch to cut Dune into a much shorter, more traditional Epic Savior Hero film.

The final product is now, after forty years, fairly well known—a perplexing two hour and seventeen-minute head-scratcher with awkward exposition and odd voice-over narration taking the place of several minutes’ worth of cut material, awkwardly paced, with the feel-good “rain on Arrakis” Kwisatz Haderach Messiah ending. (This was not originally how the film was supposed to end, and it certainly isn’t how the book ends.) Since the studio took control of the final cut before the visual effects production was done, there is famously not enough completed footage that could be used to reconstruct a director’s cut even if Lynch were interested in making one. (A 1988 version of the film—the “Alan Smithee” version, done without Lynch’s involvement—that restored cut material without finished visual effects that aired on independent TV stations in the US had to make do in some portions with still artistic drawings and lengthy voiceover narration.)

Masterpiece abounds in anecdotes from numerous people who participated in making Dune—actors Kyle MacLachlan, Sean Young, and Alicia Witt and costume designer Bob Ringwood are especially memorable. But the main character of the book is obviously Lynch himself, who we encounter through the anecdotes of others in his first picture for a major Hollywood studio, losing creative control bit by bit. The experience was, by all reports, deeply traumatic for Lynch, and he famously says as little about it as possible in public (except that it taught him never to surrender the right of final cut). Predictably, then, Masterpiece does not include much from Lynch himself—the book’s coda, after over 500 pages, is a brief three-page discussion with Lynch that does not really offer much that he hasn’t said publicly before. This isn’t the fault of Evry’s book, though. It does a remarkable job of putting together interviews with a lot of people, most of the Dune team in fact who are still alive and willing and able to talk frankly about a forty-year-old film production. (Alas, there are no interviews with Patrick Stewart here, although I am told that Stewart’s recent memoir Making it So relates Stewart’s experiences acting in Dune.)

If anything Masterpiece is, as a book, too comprehensive, too encyclopedic. The book seems to be aware of this fact—a foreword to the reader who isn’t interested in reading the whole thing gives advice on which parts she should read depending on her interest. I give kudos to the publisher for its willingness to produce a book of this size and production quality. (The copy I have is a hardcover with red foil page edges, a ribbon marker, and a forty-page photo insert, all of which is printed on heavy, high-quality paper.) In some cases, though, its ambit of trying to stuff all it can about Lynch’s Dune between two covers wears thin, especially in the last fourth of the book which discusses the film’s legacy. The chapter on subsequent cultural references to the film, for instance, reads like a more elaborate version of the “References in Popular Culture” section of a Wikipedia page. However, I can recommend this book, not only to fans of the film and of David Lynch, but also to anyone who is interested in the process and the challenges of adapting a literary work for the cinema. If that process fascinates and mystifies you as much as it does me, A Masterpiece in Disarray will give you a lot to think about.

[1] As a critical aside, it took the Star Wars franchise forty years—that is, until Rian Johnson’s Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (2017)—to make a tentative foray at grappling with the problems inherent in the Epic Savior Hero narrative, especially when it plays out in a diverse, technologically sophisticated world. In other words, the very element of Dune George Lucas didn’t steal. And what happened? The film critics seemed to like it, but “the fans” (and the “paid a lot of money to be consistently wrong” Ross Douthat) raised such a hue and cry that the next film basically pretended that none of The Last Jedi even happened. Not even Lucasfilm can make, or seriously wants to make, “Star Wars for adults.”