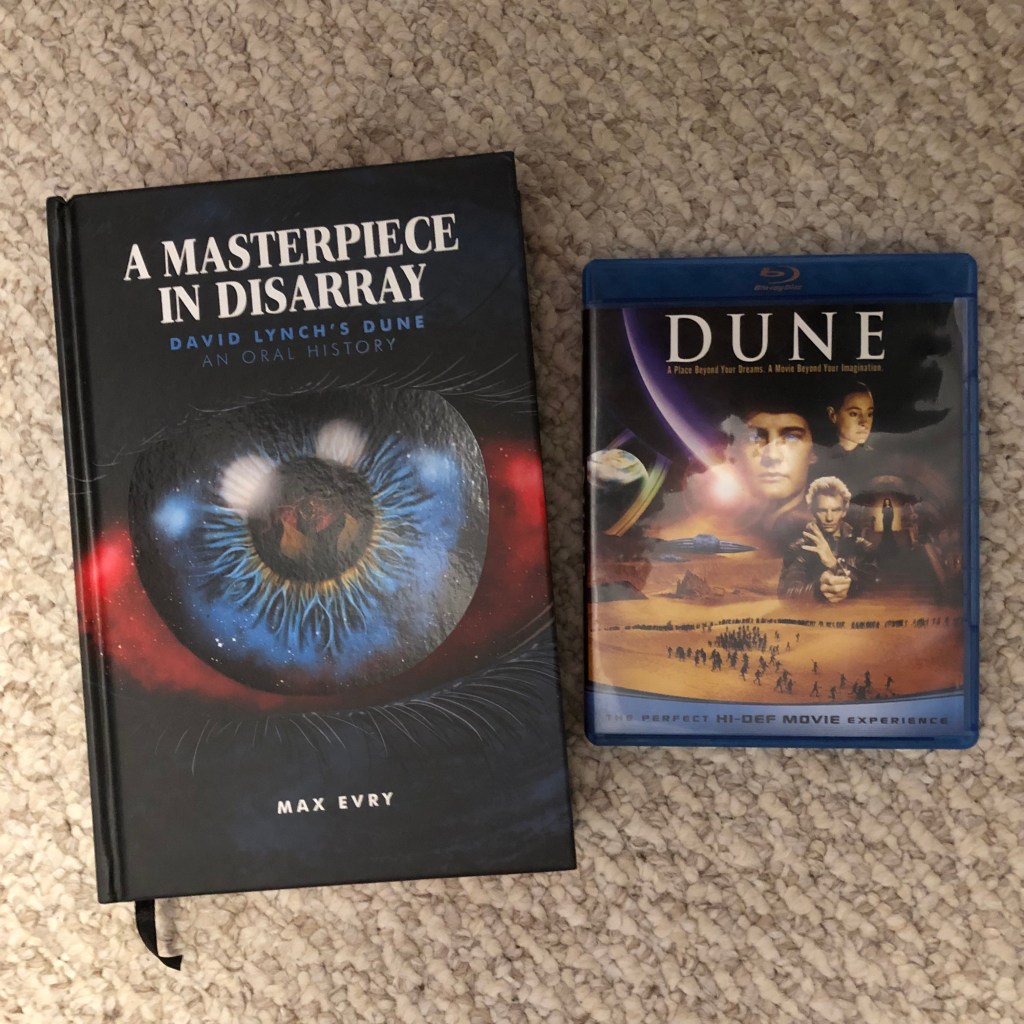

Last Friday, my son and I attended the opening night of Tron: Ares, the third installment in the Disney computer movie franchise. (The CGI one, not The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes.) Readers of this blog are well aware of my somewhat irrational 80s-kid love for the 1982 Tron and its 2010 sequel, Tron: Legacy, so it’s no surprise that I would be on hand for its opening night, watching it in IMAX 3D, no less.

Having watched it, I can say that while Tron: Ares is certainly a sensory spectacle, it isn’t the strongest film in the franchise, which, depending on your feelings about the first two movies, may not be saying much. Behind the sunny optimism that prevails at the end of Tron: Ares is a bleak counsel of desperate surrender in the face of the very forces that are pulling the world apart.

***

Warning: Spoilers for the movie follow.

As Tron: Ares opens, we find that ENCOM, the software company featured in the 1982 and 2010 films, is locked in a technological race with recently spawned competitor, Dillinger Systems. Both companies are in a race to develop technology that will allow them to synthesize virtually any object using modified versions of the particle lasers that, in the first two films, beam people into the virtual world. The lasers work like 3D printers, printing everything from orange trees to super-hardened military hardware, and they can even create embodied real-world avatars of programs akin to the ones that populate the virtual world of “the Grid,” the long-standing designation in the Tron universe for the inner world located inside computer networks.

There is one catch to this amazing synthesizing technology, though: both companies have hit a theoretical limit for how long their creations can endure in the real world. After twenty-nine minutes, the created objects, no matter how simple or complicated they are, crumble into pixelated dust.

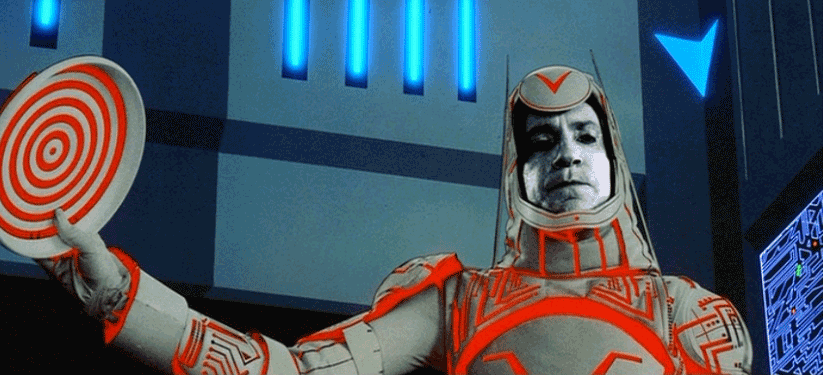

However, ENCOM and its young CEO Eve Kim (Greta Lee), have an advantage: they know where to find the “Permanence Code” that would allow these synthesized objects to last indefinitely. Julian Dillinger (Evan Peters), the whiny, temperamental CEO of ENCOM rival Dillinger Systems, desperate to win lucrative military contracts, will stop at nothing to get the Permanence Code from Kim. So, Dillinger fires up his 3D-printing laser matrix, works up avatars of his master control program, Ares (Jared Leto), and Ares’ chief lieutenant, Athena (Jodie Turner-Smith), and sends them to collect the code from Kim. (In twenty-nine minutes or less, of course.)

Here, though, Ares begins to have realizations that Dillinger didn’t prepare for. Ares is an AI computer program, and in the course of his training (since our current expectations of AI is that it has to be trained iteratively) he has developed curiosity about the real world as well as feelings, and more than anything a desire to be something more than just a program carrying out the imperatives of Dillinger. Dillinger, though, makes it clear that however much he values Ares’s support, he views Ares himself as expendable, and Dillinger obtaining the Permanence Code will not change that. So, rather than execute Dillinger’s order, Ares abruptly changes sides and joins forces with Kim to keep the Permanence Code out of Dillinger’s hands.

After a fairly convoluted series of events, which include Kim and ENCOM beaming Ares into the preserved Grid from the original 1982 Tron (silly but fun for the fans) and becoming himself imbued with the Permanence Code by the preserved avatar of no less than Kevin Flynn himself (Jeff Bridges, reprising his role in the first two Tron films with the same gee-whiz tics he’s been using since 1982), Ares returns to the real world as a messianic figure. The change registers visually by the neon highlights on Ares’s suit turning from red to white, much like Gandalf the Grey returning from the other side of death as Gandalf the White. But the movie has tried to telegraph this messianic moment from the very beginning; Jared Leto’s Ares spends the entire film with shoulder-length hair and a beard that makes him look like a youth pastor at a seeker-sensitive church cosplaying Jesus, after all. Permanence Ares, together with Kim, ultimately save the day, Dillinger’s world crumbles around him, and order is restored. Kim and ENCOM go on to use the Permanence Code to synthesize, not military hardware and supersoldiers, but instead things that solve the problems of humanity—feeding the hungry, curing cancer, things like that. All’s well that ends well!

***

There is a certain techno-optimism baked into the basic premise of all of the Tron movies that is hard to maintain in the enshittified world of 2025. In this sense, Tron: Ares is as much a victim of the desperately long timeframe it took to move from development to production as anything. Older, more quaint techno-optimism notwithstanding, the core of the thematic appeal (such as it is) of the first two movies is a search for transcendence beyond technology. At the core of the original Tron movie is the struggle against the nakedly totalitarian Master Control Program, whose mission is to usurp the role of the human users and to bend all computer programs to its will. (True to its roots in the Cold War Reagan-era United States, Tron represents the MCP as ideologically bent on destroying the “religion” of the users, much like the aims of the religion-destroying Soviet Union as reflected in Western propaganda. The MCP’s lieutenants and minions even glow red.) Tron and Flynn win out over the MCP and hence restore the natural subservience of program to user to the Grid. The “religion of the user” flourishes once again, and programs are once again just useful tools for humans to use.

Tron: Legacy takes the same theme in a new direction. Now it is Kevin Flynn, the hero of Tron, who has succumbed to the proto-totalitiarian impulse to create what he terms the “perfect system” that will (somehow) help humanity to overcome the imperfections of the real world. He disappeared in 1989, leaving behind his son, Sam Flynn, to grow up fatherless and alienated. In the course of following up clues as to his father’s ultimate whereabouts, Sam learns where his father is, why he left, and what he has learned in the course of his enforced captivity inside his own Grid. He has learned that his desire to implement the perfect system, implemented by sentient program Clu, was chimerical because it led him to devalue his relationship with Sam and to abandon the imperfect, but irreplaceable, real world. It also led to the destruction of the Isos, “isomorphic algorithms” which spontaneously and unexpectedly manifest within the Grid, showing Flynn that perhaps the messy imperfection he sought to repress is ineliminable from even the Grid itself. Of all the Tron movies, Tron: Legacy comes closest to speaking to the social pathologies of current Big Tech while at the same time portraying a set of humans with legible, human-sized motivations and struggles.

The trajectory of Ares from Dillinger’s master control program to messianic program at large in the real world is, I think, meant to explore a similar theme to that of Flynn’s enlightenment in Legacy. The problem, though, is that Tron: Ares underdevelops the theme. Some of that is due to Jared Leto’s limited acting range: he plays Ares with the flat affect of HAL-9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey and doesn’t let us into Ares’ internal conflict. The real limitation of Tron: Ares, though, is that Ares’ enlightenment and defection is just one more plot point in the service of, at bottom, a straightforward, but utterly overstuffed, white-hat/black-hat techno-Western. The movie rarely gets a chance to breathe, to allow us to sit with the characters and develop any sense of what is at stake for them, and for us as the audience. In the midst of all this, Ares remains ultimately a handsome cipher with fearsome combat skills. Mindless wall-to-wall action is fine if you’re in a Fast and Furious movie that isn’t even trying to be credible. But for all its winks and nods to the Tron nostalgists out there, Tron: Ares ultimately lacks any sense of humor about itself.

What is really at stake in Tron: Ares is, despite the title, not Ares—his trajectory is really just a sideshow—but instead a struggle between two tech CEOs for corporate dominance. If you’re a tech CEO, I guess that plot really speaks to you, but otherwise, not so much. Of course, the movie seeks to engineer our loyalties at every turn. ENCOM, the white hats of the piece, are the geeky, fun, diverse company who is seeking the Permanence Code to help solve the world’s problems. Eve Kim is not only a nice, relatable woman, but is also grieving her dead sister and trying to use the Permanence Code to further cancer research in her sister’s memory. ENCOM’s color palette is all warm blues and its design sense is curvilinear and organic. Dillinger Systems, by contrast, is all angry reds, blacks, and grays and boxy, angular, spiky designs. Julian Dillinger is a peevish brat with a genuinely unhealthy relationship with his domineering mother (Gillian Anderson, trying her level best with this part),[1] and Dillinger wants the Permanence Code to develop a next generation of unstoppable weapons of war and supersoldiers.

The difference between our protagonists and their spheres of influence is not remotely subtle. And yet, they are both ultimately just tech CEOs struggling for corporate advantage. We are supposed to derive comfort from the fact that the good CEO wins out over the bad CEO. But at the end of the day it’s all just CEOs—and of course, Permanence Ares, who ends the movie wandering Mexico on a motorcycle learning about human life. Nice work if you can get it.

It’s hard to derive much solace in 2025, though, from a movie that tells us that the only thing that can stop a bad tech CEO is a good tech CEO. We are living through the reality that there really aren’t any good tech CEOs, certainly none with the power and influence wielded by the real-life analogues of Julian Dillinger. Instead of the messianic promise of AI becoming sentient like Ares and trying to affect a rapprochement between the imperatives of technological growth and the claims of humanity, we have people like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel who have thrown their lot in with authoritarian government, genocide, and carbon-induced climate disaster. We even have Thiel giving private, secretive lectures which, in the absence of any historical or theological evidence or warrant, claims that opponents of AI are servants of the antichrist. It’s hard to be celebratory about the actual state of AI technology; far from curing cancer and synthesizing orange trees on the Alaskan tundra, it’s turning most of the Internet into a soup of misinformation and poorly written slop, jacking up electricity prices, and hastening our ongoing climate catastrophe, all to help college students cheat on writing assignments and to save mid-level office workers a few minutes a day in writing meaningless reports.

Tron: Ares has precisely nothing to say to any of these actual problems. That would be fine if it were just a big dumb action flick. But it isn’t; whether it wants to be or not, it’s a film about tech CEOs and AI screening in 2025 in a world set on fire in large part by the very forces it celebrates. It’s impossible not to have a sense of the tonal disconnect between the sunny world at the end of this movie and the one in which we find ourselves, and it’s hard to swallow the answer this movie proposes, which is the non-choice choice of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan:Don’t like your absolute ruler? Start again with a new absolute ruler and hope for the best!

***

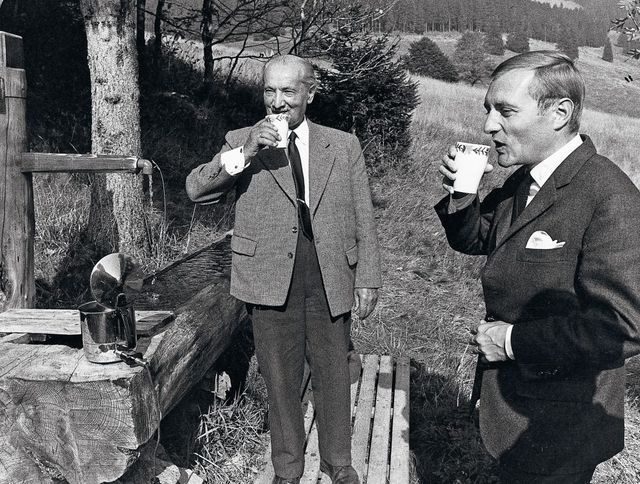

In 1966, Martin Heidegger, the first Nazi rector of Freiburg University and also an influential philosopher, consented to an interview with the German newsweekly Der Spiegel in which he agreed to break his longstanding silence about his complicity with the Nazi regime. In the interview, only published five days after Heidegger’s death in 1976 by Heidegger’s stipulation, Heidegger is famously evasive and misleading on the subject of his tenure as a Nazi official, seeking instead to paint it as a sadly misdirected application of his philosophical thought. Striking a quietist pose reminiscent of the late Hegel’s famed statement that “the owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk,” Heidegger tells his interviewers:

[P]hilosophy will be unable to effect any immediate change in the current state of the world. This is true not only of philosophy but of all purely human reflection and endeavor. Only a god can save us. The only possibility available to us is that by thinking and poetizing we prepare a readiness for the appearance of a god, or for the absence of a god in [our] decline, insofar as in view of the absent god we are in a state of decline.

In a strange irony, the decidedly anti-technological thought of the late Heidegger became a seminal influence on the intellectual ethos of Silicon Valley. The quietist project of preparing for the advent of a god that Heidegger espouses in his Spiegel interview becomes, in the hands of today’s tech overlords, an effort to “move fast and break things,” to “disrupt,” to force history open at its joints so that the god may enter. Tron: Ares is 2025’s cinematic depiction of the current state of this half-baked Silicon Valley messianism. If anything, the emptiness of the film may have ultimately done us all a favor: the digital messiah for which our tech overlords have prepared us is, like Jared Leto’s Ares, probably nothing but a vapid bore.

[1] I, for one, sensed shades of the vaguely incestuous Raymond Shaw/Eleanor Iselin dynamic from the 1962 adaptation of The Manchurian Candidate in that relationship. The movie barely devotes any real interest to it, though, and in the process wastes Gillian Anderson’s talent.