I am currently feeling under the weather in a way that has me waking up at 3 am feeling slightly feverish. Sometimes my febrile state bubbles long-standing thoughts up to the surface. At 3 am this morning, it was this:

English seems to be an outlier in the European languages in the way it refers to a physically reproduced impression of a book.

The common word for an individual impression of a book in English is “copy”: “The book sold one million copies”; “I bought two copies of the book, one for me and one for a friend”; and so on.

Many European languages, though, use a different word for an individual instance of a book. For instance:

French: exemplaire

German: Exemplar

Spanish: ejemplar

Portuguese: exemplar

Now, all of these languages also have a word for “copy” (Fr. “copie”; Gr. “Kopie”; Sp. “copia”; Pr. “”cópia”). It’s just that the word is not used, or exclusively used, to refer to printed books. The dictionary of the Real Academia Española attests to the use of “copia” to refer to individual printed books (although it’s only the ninth of ten definitions!) and I think Italian may use its word “copia” this way also. But French and German, to my knowledge, almost never refer to a printed book as a “copie” or “Kopie” and almost always as an “exemplaire” or “Exemplar.”

In all of these languages, the cognates for “copy” connote an object that endeavors to reproduce as faithfully as possible all of the visible properties of an object. So, for instance, a copy of a painting in French would be a “copie.” Copies made by a Xerox machine would in German be a “Photokopie.” And so on. The implication is, I suppose, that typeset books aren’t “copies” of an author’s original manuscript in this sense; they don’t exactly reproduce the manuscript’s pagination, handwriting or typeface, etc. The word for “copy” in these languages also carries the negative connotations that “copy” in English sometimes carries, implying something fake, phony, knocked off, not as good as the genuine article.

The “exemplar” words in these languages do not, however, carry any of these negative connotations of phoniness. Their semantic range is limited to describing individuals of a similar or like kind. Individual copies of a printed book are obviously as nearly identical to one another as can be achieved, and so the individuals are “exemplaires,” “Exemplare,” etc. These words are also used to describe individuals in a species of animals, which obviously differ among themselves but have common species-related characteristics. In English, we tend to use the word “specimen” for this, if we use a specific word at all.

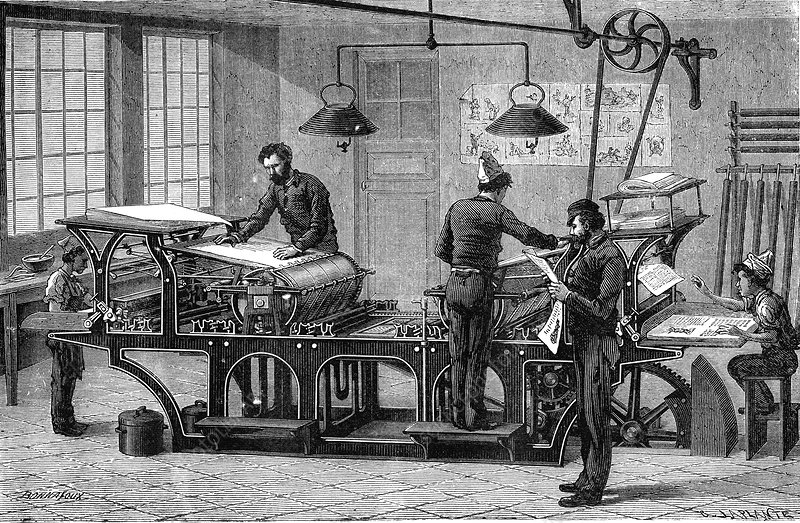

As far as I can tell, the European languages refer to manually produced (not printed) instances of a book or other writing as “copies.” So books produced before the advent of the printing press, copied by hand by scribes, could be referred to as “copies,” although modern usage may also refer to them as “exemplars.” Manuscript copies of a book or writing done by an author would definitely be referred to as “copies,” as they would be in English. Referring to the individual instances of a book as “exemplars” appears to postdate the advent of the printing press in Europe.

In English, however, these distinctions which European languages use different words to track all get subsumed under the wide semantic umbrella of the single word “copy.” Manuscripts of ancient books are “copies”; forged artworks are “copies”; individual bound volumes of Dan Brown novels for sale at the airport are “copies.”

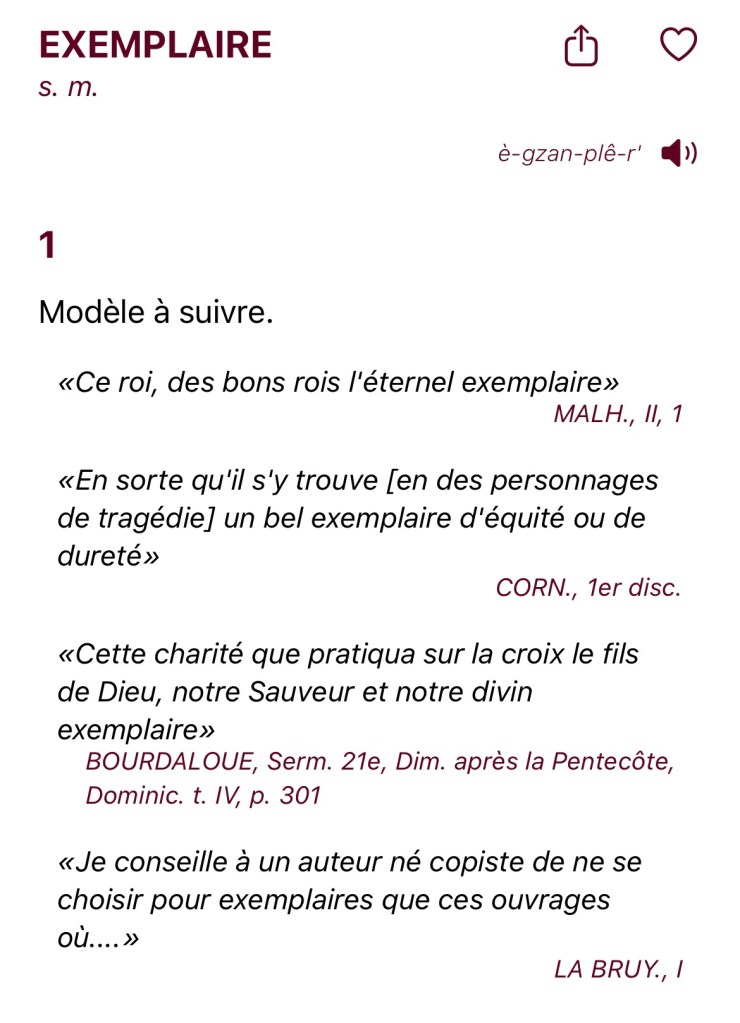

English of course has its own word “exemplar,” but it’s extremely rare or odd to hear it applied to individual books. In common parlance it is most often applied to people, not animals or things. It means something more like “ideal,” “paragon,” or “role model”: not just a copy, not even just an example, but an instance of something or someone so characteristic, so perfect in its kind, that it takes on a special status. An exemplary status! To my knowledge, the European languages don’t commonly use any cognate of “exemplar” to describe such a thing or person. (Littré’s major dictionary of French usage cites 16th- and 17th-century uses of “exemplaire” as a noun in this sense. Le Dictionnaire Robert gives this sense as a second separate meaning of “exemplaire” as an adjective with meanings similar to “exemplary” in English, but includes no substantival use of “exemplaire” in this sense.)

There is one minor, but telling, exception to this. In Spanish and Italian, and possibly in some other languages, their cognate word for “exemplar” can be used to refer to a story or other example which conveys a moral or a warning to the reader or hearer. The Novelas ejemplares of Miguel de Cervantes use “ejemplar” in this sense. English has its own word for this, “exemplum,” which is quite rare and is derived directly from Latin. We do have shades of this meaning from other words and expressions in English: “exemplary punishment,” “making an example of someone.” From the 17th century onwards German used the word “Exempel” for this, although my understanding is that over the centuries this meaning, to the extent that it is still there, has become mostly absorbed into the more common German word for “example,” “Beispiel.”

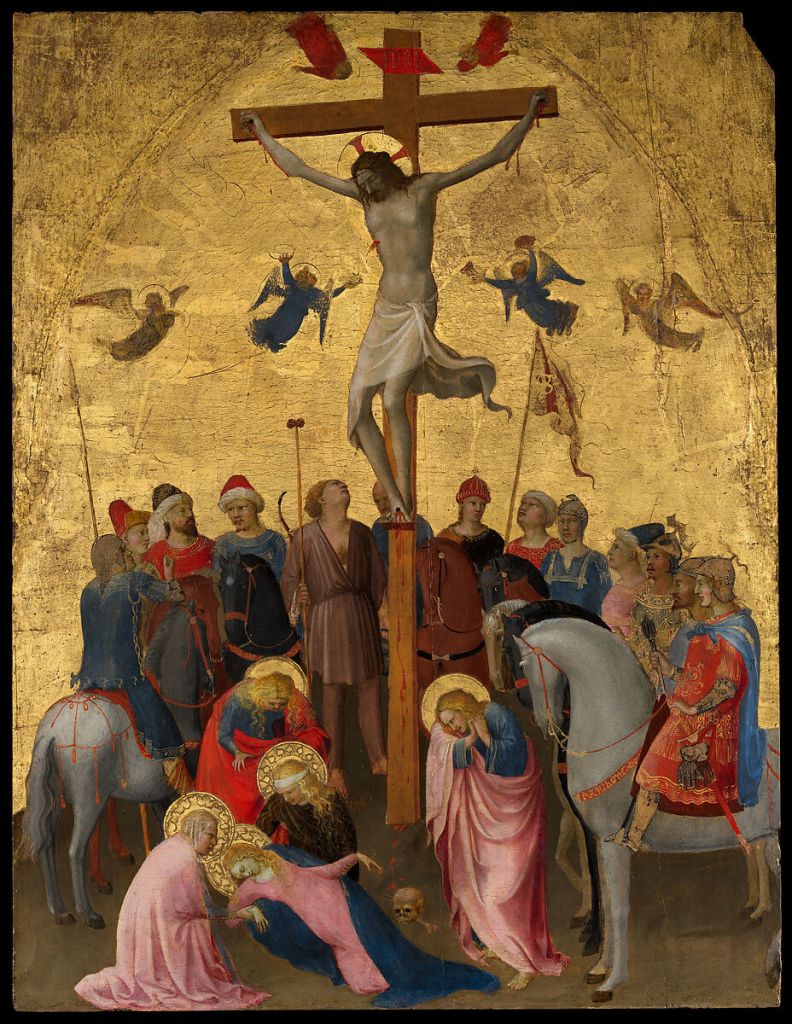

“Exemplar” in English also has a long-standing technical meaning in philosophy and theology to refer to an “idea” or “ideal object.” “Exemplarism” refers to a conception in medieval Christian philosophy whereby God creates and manages the world by means of eternal archetypal ideas in the divine intellect—exemplars—that are part of the divine nature. It’s also sometimes used to describe the theory of atonement from Peter Abelard through Protestantism in which Christ is sent to the world as an example to humankind, rather than as a substitutionary sacrifice. In the current philosophical world, dominated by work in the English language and only dimly aware of history, exemplarism is used by Linda Zagzebski and others to describe a moral theory in which the following of moral examples and imitation of exemplary persons can furnish a complete ethical theory. Since philosophy and theology are relatively transnational (and also somewhat insular) pursuits, this use of “exemplar” and “exemplarism” persists in philosophy, theology, and history written in the European languages. But this usage is only tangentially related to the wider usages of “exemplar” and its cognates to refer to books and moral examples.

What does all this linguistic and conceptual history mean? I haven’t been able to do the really deep dive into etymology required to tease out all of the relevant history. But at a glance it appears to me that sometime around the advent of mechanical reproduction of books in Europe, the languages on the continent responded to an unspecified pressure to distinguish printed books from “copies.” Perhaps it was to avoid the negative connotations of phoniness or untrustworthiness inherent in mere “copies.” For whatever reason, English did not respond to this linguistic pressure. The usage and development of its word “exemplar” trotted off in its own direction largely unknown on the continent, only intersecting occasionally in technical usage in the recondite precincts of international philosophy and theology.

I don’t know all of the European languages, and I don’t know the ones I know as well as I would like! If you know and speak a language of European origin and have read this far, what is your experience with this cluster of words for talking about books? Do you know any of the etymological and historical links missing from my account? Have I misstated relevant facts? Let me know in the comments!