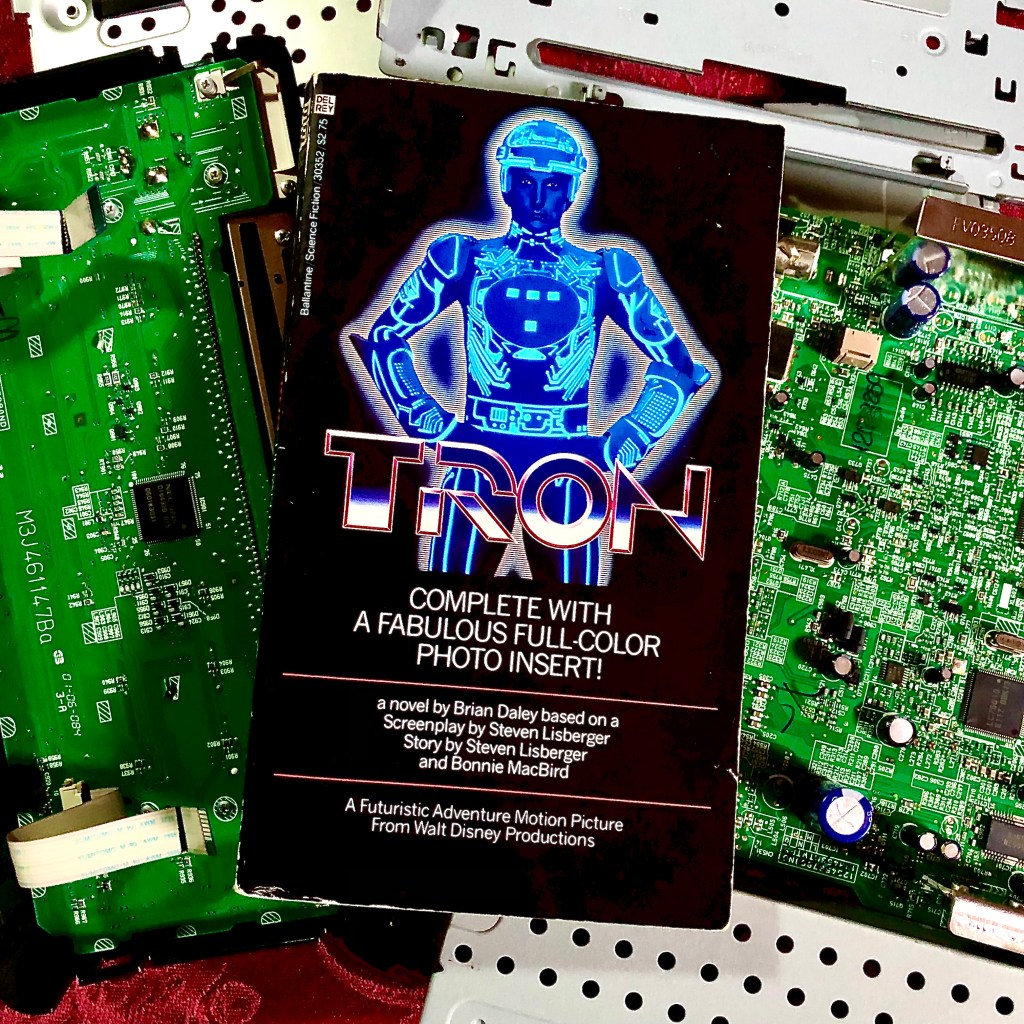

Daley, Brian. Tron (Ballantine, 1982). Adapted from a screenplay by Steven Lisberger and a story by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird.

Narratives in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Book and film critics have spilled a lot of ink on the subject of film adaptations of books. Spike Jonze even made a (hilarious, absurd) movie satirizing the process. But what about the reverse process: taking an original screenplay and adapting it as a novel?

I am just old enough to remember when it was commonplace for films made from original screenplays to release a “novelization” of the film that coincided with, or just preceded, the release of the film. Before the advent of streaming services that allow anyone with a subscription to watch movies anywhere on their phones, before the advent of VCR’s and rental videocassettes even, studios sponsored film novelizations to promote their films. The concept was simple: a film novelization, usually a mass-market paperback, is portable and readable anywhere, letting fans connect to a movie they like without having to drop everything and go to a movie theater. The novelization is also one more artifact about the movie circulating out in the world, on bookstore and magazine rack shelves, in the hands of readers on the bus or in a doctor’s office.

Suffice it to say that film novelizations are not, and were never really meant to be, great literature. They are mass-produced promotional objects on a level akin to Mcdonald’s movie tie-in drinking glasses. I do have a soft spot for them, though, as they represent a feature of the pre-Internet, pre-personal-computer days of my childhood that are increasingly hard to remember or even imagine.

I didn’t own a lot of film novelizations personally. The one I remember best was the 1986 novelization of Top Gun by Mike Cogan, which I know I read six or seven times. (Don’t judge me; it was a strange time in my life.) My fondest memory, though, is of the novelization of Tron, the widely-panned 1982 Disney sci-fi film starring Jeff Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner, and David Warner.

The Program, The Myth, the Legend

Tron was released on July 9, 1982 to a great deal of hype. If you don’t know anything about the movie, the short synopsis is that Kevin Flynn, a computer hacker/programmer, gets blasted into the world of the computer—called the System—by the tyrannical Master Control Program, or MCP, an artificial-intelligence program run amok. Inside the System, Flynn helps Tron, a heroic program written by Flynn’s friend Alan Bradley, overthrow the MCP and restore freedom to the System. It was the first film I know of that made extensive use of 3D-rendered computer animation, most of which was rendered painstakingly frame-by-frame. It was the gee-whiz visuals that Disney used to sell the movie, and understandably so; they were unlike anything that had ever been on screen up to that point.

I was about to turn eight years old in 1982 and as a geeky little boy of course I wanted to see Tron desperately. Life, though, had other plans. My family took a trip to Disney World in the summer of 1982 to celebrate my older sister’s tenth birthday, and on our down time we went to see movies. The theatrical competition for Tron was John Huston’s adaptation of the Annie musical with Carol Burnett and Albert Finney and the Steven Spielberg blockbuster E.T. The family opted to see the latter two movies. No one in my family besides me had the slightest interest in seeing Tron. (Well, my father might have, but he wasn’t with us on that trip, and anyway I only remember going to the movies with him once. It was Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, which played a matinee in my hometown movie theater when I was four or five. We walked out.)

What I did get as a consolation prize, though, was the novelization of Tron, by Brian Daley. I have no recollection of exactly where my parents bought it for me, whether on our Florida vacation or later. But I loved having it. It had a color insert of post-production stills from the movie that showcased the CGI animation. I do not recall ever actually reading the book; having it as an artifact on my bookshelf was enough, at least until I could see the movie itself.

Tron ultimately came to be lampooned as a bomb at the same time as it had a sort of geek cult following, probably due to its aesthetic and its place in the history of CGI animation. Its biggest weakness was that it was just not that great a movie. The story had problems that went beyond the simple suspension of disbelief required to accept Jeff Bridges/Flynn getting blasted into the world of the computer. The dialogue was clunky, especially Flynn’s; Jeff Bridges did his best, but some of what the movie has him exclaim is as incongruous as Pavement lyrics. The light-cycle sequence, the first sustained CGI sequence in the history of film, is genuinely thrilling, but it’s a set piece packed away in a lot of turgid struggle between the MCP, his chief lieutenant Sark, and their red-clad minions with the glowing blue forces of good. The chief axis of the struggle is over, oddly enough, something like religion: the MCP seeks to quash programs’ belief in the Users, the beings in the world outside who write and use the programs, and the blue-clad good guys are those who stubbornly refuse to renounce their belief in the Users and hence get pitted against the MCP’s Warrior Elite (and each other) in gladiatorial combat.

This element of Tron echoes late-Cold-War anti-Communist ideology (the dastardly, power-hungry Reds demanding that everyone renounce faith in a higher power and worship them as lords and masters), but the ideology of the movie is too vaguely rendered to serve as a transparent allegory. This is largely because of the added element Tron introduces of unease over advanced computer technology run amok, a concern that cuts across the conflict between capitalism and communism. In this Tron was a movie ahead of its time. In 1982, hardly anyone had a personal computer, much less one capable of networking with other machines, and AI was still the stuff of sci-fi stories. Tron was a cautionary tale about techbro anarchocapitalism decades before anyone thought that was something we might need to fear. But the movie almost tries to be too much in too little time: gee-whiz adventure, Star Wars liberation fantasy, allegory. It doesn’t quite succeed at any of it.

The Novel and the Film

Brian Daley’s novelization, though, is in some important ways superior to the film. I don’t know what specific process Daley used to write this book, but commonly the studio would give the author some more or less final version of the screenplay, plus perhaps some conceptual art, production stills, or other visual references, and then the novelist would make a book out of that. Given the need for a novelization to come out at the same time as the movie, there would normally be no time for the writer to see a finished cut of the movie before writing the book. This means that sometimes novelizations include dialogue, entire scenes, or entire subplots that ultimately get cut out of the theatrical version of the film. Even if the screenplay the novelization author uses as a basis for the novel, though, tracks the final cut of the film perfectly, the author inevitably has to use a certain amount of license in turning the story into a readable novel. The conventions of fiction writing for a popular audience demand a certain amount of characterization and expansion that a “show, don’t tell” screenplay simply don’t provide.

I know the movie Tron well—it’s one of those movies like David Lynch’s 1984 Dune that I love, even as I realize how flawed they are—and so I looked forward to the possibility that the book would tell a richer story than the film. In that I was not disappointed.

The story of the Daley novel and much of the detail does not depart radically from the theatrical film.[1] Flynn’s dialogue is as jarringly absurd as ever—I guess Daley felt he couldn’t entirely rewrite dialogue that would end up in the film. Also, the new scenes or story elements portrayed in the book that are not in the movie are of only minor significance.[2] Where the book oustrips the theatrical film is that it sheds new light on the characterization and motivations of certain characters, as well as certain story elements that are certainly implicit in the film but are so implicit as to be scarcely legible.

The most significant of these advances:

The character of Ed Dillinger. In both the book and the film, Ed Dillinger (David Warner), whose counterpart in the System is Sark, the MCP’s Command Program, is a menacing, power-hungry thief. Dillinger rose to Senior Vice President of ENCOM by stealing Flynn’s ideas and code for Space Paranoids and other highly profitable video games, hiding the evidence of his theft, and steering Flynn to the exits. He had a hand in creating the MCP, but he learns in the course of the story that the MCP has developed plans of its own and that it will brook no resistance from Dillinger or anyone else to its execution of those plans.

In the book, though, we get more of a window into Dillinger’s state of mind—an easier feat in a novel than in a movie. The novel’s Dillinger is putting on a brave front, but is secretly terrified both that Flynn will find the evidence he needs to prove Dillinger’s theft and of the MCP, which is spiraling out of control. David Warner is a fine actor, but for whatever reason his performance as Dillinger doesn’t capture this vulnerability and fear very well. At least I don’t think so.

The character of Lora/Yori. Lora (Cindy Morgan), a researcher working in ENCOM’s laser lab, doesn’t have a lot to do in the movie other than being the current girlfriend of Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner) and Flynn’s ex.Her counterpart in the System, Yori, is a program working in an unnamed sector near the Input/Output Tower manned by Dumont. She is Tron’s love interest (Tron, of course, being Alan Bradley’s System counterpart), and she helps him, but beyond that she doesn’t do much.

In the novel, though, we get a little more discussion of Lora’s different feelings for both Bradley and Flynn. (Not much more, though, and her conflicted feelings make her seem more than a little indecisive, but this is the character Daley was dealt.) Yori, however, gets even more of a backstory. Yori used to work in the Factory Domain of the System, a domain described as a hub of productivity before the MCP began draining it of power and resources to feed its own designs (see below). She and the programs of the Factory Domain used to do amazing work for the Users, but now they are systematically starved and reduced to dronelike servant labor. They are continually weak and semiconscious, and their speech consists of little beyond strings of numbers. (I see echoes here of the dronelike inhabitants of Planet Camazotz in Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time.)

In the movie, Tron, upon reuniting with Yori, re-energizes her, and only then does she recognize him. The same thing happens in the book, but the book explains that Tron is able to do so because he has drunk from a pure source of power that he, Flynn, and Ram found after escaping the Light Cycle grid. The MCP, we learn, has either tapped dry the standard sources of power or else diluted or polluted them. The MCP overlooked this power source, though, and it is a rare source of “true” power, providing Tron with clean, good power to spare. This earlier scene also happens in the movie too, but without much explanation of its significance. Hence when Tron reenergizes Yori, the movie leaves the reason why it happens obscure; we are left wondering if it isn’t just her love for Tron that does it. I have watched the movie any number of times and never once thought of connecting the Tron/Yori reunion scene with the “drinking the pure power” scene.

Yori’s “worker” attire in the Factory Domain is described in the book much as it is shown in the movie: boots, tight-fitting cap. What the movie does not portray, though, is that in the book the “reenergized” Yori is able to transfigure, as it were, into a non-worker-drone form. This transfigured Yori is described almost like an angel, shining with light, long tresses hanging downward, in refulgent robes. She transfigures multiple times in the book, but always reverts to “worker” Yori for action scenes.

Lora/Yori is, as a character, still underutilized and largely lacks agency. She is there to humanize the male characters a little bit. She, and the movie, definitely fail the Bechdel test, not least because she is the only woman in the whole film.

The MCP’s relationship to the System and to the real world. As in the movie, the MCP is a megalomaniacal artificial intelligence that has decided that it can run the world better than its human creators. (With the benefit of hindsight it is hard not to see it as a mirror for “there is no alternative” technocratic neoliberalism run amok, but I digress.) Another underplayed element in the movie that Daley’s novel highlights is that the MCP’s hunger for power is also a literal hunger for energy. The MCP’s project of harnessing the power of other programs, like cryptocurrency mining, takes a lot of electricity, and the novel makes clear that the MCP gets it by tapping every energy source it can find (drill, baby, drill!), siphoning off energy that existing sectors need to function, and polluting the rest. The novel ties the lethargy of the Factory Sector, barely remarked in the film, directly to the MCP’s energy vampirism. The novel also explains certain parts of Flynn, Tron, and Yori’s ability to evade the MCP’s forces by saying that the MCP is distracted, operating near the limit of its processing power in pursuing its plan of world domination.

In the final confrontation between Tron and the MCP, the film depicts, in a few fleeting frames, figures pinned to the inside of the retaining ring hiding the MCP’s central conical head. In another case of added context, the novel explains that these figures are Dumont and other Input/Output majordomos—the high priests, as it were, of the religion of the Users—and that the MCP is draining their energy to power himself. It’s an added phantasmagoric detail that makes the MCP that much more horrific: he surrounds himself with the crucified, dying bodies of the priests of his enemies and lives off of their life force.

In the real world, the MCP of course does not have the same sort of powers as in the System. The novel, though, underscores the MCP’s main real-world power—the power of surveillance—in a way that, again, the film underplays. Many scenes that take place in ENCOM Tower in the film include cuts to footage of characters walking hallways taken from the screens of security cameras. These images in the film certainly add to the conspiratorial, claustrophobic air of ENCOM Tower, but do little more than that. In the novel, though, the MCP is monitoring all of this security footage and knows more or less where all of the principals are in the building—and possibly elsewhere.

Style, and a Little More Substance

Tron the film is arguably a triumph of style over substance. Its visual aesthetic and its pioneering use of CGI are by far its greatest contribution to cinema and visual art. It might seem strange, then, to devote attention to the novelization of Tron. The novelization is a competent, decently plotted piece of storytelling, but hardly innovative as a work of fiction. It’s a novel, and not history-making in any way. Why read it, much less discuss it?

For me, reading the novel gave me insight into how Tron the film could have been better than it was. As my above discussion makes clear, so much of the additional substance and context the novel provides is clearly implicit in the finished film, just underdeveloped. The screenplay spelled out some, but not all of this original context, and the novel took it further. A few changes in how certain elements of the story got told—not all of which would have added to the movie’s run time—might have made the actual story of the film more legible underneath the computer graphics.

No version of Tron—screenplay, novelization, film—is great storytelling. Both the in-world stakes of the central conflict between the MCP and the “good guys” as well as its messages about technology and ideological conflict are too ambiguous to be compelling. Movies go through a torturous process on their way to the screen, and in the case of Tron the end product yielded a more cramped story than most. Reading the novelization of Tron is a great reminder of, among other things, the limits of the auteur theory of cinema; films are the outcome of the creative labor and business decisions of large teams of people, and all of those influences leave their mark on what ends up on screen.

[1] My guess is that most of the edits to the screenplay and story were finished during the screenplay and storyboarding stage, before even principal shooting began. Animated films often work this way, and especially worked this way before the advent of relatively cheap computer animation, since full production of scenes involved armies of human beings drawing by hand. The little I know about the production of Tron suggests that it was produced very much like an animated feature due to the amount of laboriously crafted 1982 CGI.

[2] The most significant of these is a scene in which Tron, after reuniting with his love interest, the woman-presenting program Yori, in the Factory Domain, spends the night with her in her apartment. The book implies that they spend the night together and have sex, or whatever passes for sex between two computer programs, but does not graphically describe it. This scene is in the screenplay (available online), which makes me suspect that perhaps implied computer-program sex was too much for Disney’s marketing department, or else filming Yori’s transformation would have been one effects-shot expense too many.

Leave a comment